You Don’t Need a Vapor Barrier (Probably)

If there’s one building science topic that confuses more people in construction than any other, I think I’d say it’s the purposes and properties of the various control layers. I’m talking about the materials that are meant to control the flows or heat, air, and moisture. I’m going to limit this discussion to the control layers responsible for water vapor, but first, let me remind you of the article I wrote about vapor retarders a couple of months ago. If you don’t know what permeance and the different classes of vapor retarders are, go back and read it.

If there’s one building science topic that confuses more people in construction than any other, I think I’d say it’s the purposes and properties of the various control layers. I’m talking about the materials that are meant to control the flows or heat, air, and moisture. I’m going to limit this discussion to the control layers responsible for water vapor, but first, let me remind you of the article I wrote about vapor retarders a couple of months ago. If you don’t know what permeance and the different classes of vapor retarders are, go back and read it.

If there’s one building science topic that confuses more people in construction than any other, I think I’d say it’s the purposes and properties of the various control layers. I’m talking about the materials that are meant to control the flows or heat, air, and moisture. I’m going to limit this discussion to the control layers responsible for water vapor, but first, let me remind you of the article I wrote about vapor retarders a couple of months ago. If you don’t know what permeance and the different classes of vapor retarders are, go back and read it.

A lot of people think you need a vapor barrier, or Class I vapor retarder, and that it needs to be on the inside of the house in cold climates and outside in hot, humid climates. Here in the mixed-humid climate I’m in, we build rotatable walls. We put the vapor retarder on the side appropriate for the season the house will be finished, and then every spring and fall, a crew goes out and rotates all the walls so the vapor retarder will be on the correct side in both summer and winter. OK, just kidding about that. There’s no good side to put it on in our climate because we’d be wrong half the year anyway.

Anyway, what do vapor retarders do? They’re materials that limit the diffusion of water vapor through building materials. That is, they prevent water molecules in the air from diving into your walls and jiggling their way through the materials in the building assembly, eventually congregating, condensing, and possibly turning your walls into a terrarium, though probably without turtles.

But here’s the thing. Not much water goes through the materials by diffusion. If water vapor is getting into your building assemblies, it’s probably not diffusion that’s the culprit. The following two diagrams ought to prove it to you.

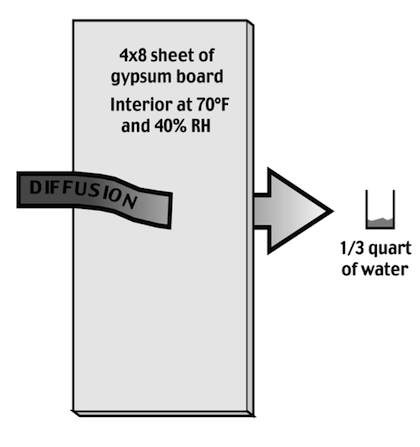

The diagram above, from the Builder’s Guides by Joe Lstiburek, shows that over an entire heating season, only a third of a quart of water diffuses through a whole sheet of drywall. The permeance of unpainted drywall is very high, generally between 20 and 90, so it’s not a vapor retarder at all.

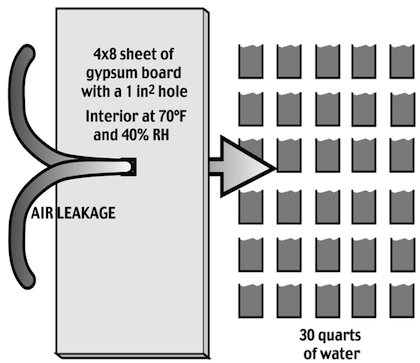

Meanwhile, air leakage through a 1 square inch hole in a sheet of drywall allows 30 quarts of water vapor to pass through the drywall under the same conditions. A third of a quart versus 30 quarts. Nearly 100 times as much water vapor goes through the hole in the drywall by air leakage than goes through by diffusion.

Moral of the story: Air sealing is more important than vapor retarders.

Not sure you believe it? I was in Maine recently talking with the Building Science Discussion Group in Portland, and out of the room full of architects, builders, and contractors, not a single one could think of a single instance where moisture problems were caused by diffusion. It’s always air leakage, they said.

Seal the air leakage pathways.

Returning to the original question about whether you need a Class I vapor retarder (i.e., a vapor barrier), if you’re getting almost no water vapor diffusing through something that’s not a vapor retarder at all, I think the answer is clear. No, you don’t need a vapor retarder, Class I or otherwise. By the time you paint the drywall, though, you’ve brought it into the Class III vapor retarder range (between 1 and 10 perms), and even less water vapor will diffuse through.

Seal the air leakage pathways.

Class I vapor retarders have their place—under slabs and in crawl spaces, for example—but for the most part, you can forget about adding them to above-grade walls. Do a good job sealing up all the possible air leaks instead.

Seal the air leakage pathways.

Related Articles

Vapor Retarder? Vapor Barrier? Perms? What the Heck?!

Meeting ENERGY STAR’s Water Management Checklist

5 Reasons House Wrap Is Not an Air Barrier

Water vapor research diagrams showing diffusion versus air leakage used with permission from Building Science Corporation.

This Post Has 14 Comments

Comments are closed.

Excellent article, Allison.

Excellent article, Allison. That has always been my train of throught. Additionally sealing between the sheetrock and the flooring behind the baseboard trim will also help to eliminate moisture and air leakage.

Yet another case for properly

Yet another case for properly applied spray foam inside of walls. catches many more air leaks than conventional batts.

Try telling that to the

Try telling that to the building department in this (central Canada)area! They make you put plastic over closed cell foam here.

Agreed, excellent article.

Agreed, excellent article. Though I was a bit confused at the end of your article, because you started off (with the title) questioning whether you needed Vapor Barriers – and you closed the article saying that Vapor Retarders (entirely different) do not have a place in walls. Wood sheathing in many conditions (including DRY) is a vapor retarder, so I think you simply misspoke?

Anyway, one of the other keys to this formula for moisture control is the existance of an air gap. If an air gap exists, then the potential for condensation exists. That’s why fiberglass walls can be more prone to condensation issues than other assemblies, and if you are spraying a wall cavity you still need to ensure there are no voids. If there is no air gap, and you have wet material, then your problems are probably much greater than simple vapor permeability. That is why we build wall systems with no air gaps at all.

Another thing some people do not understand regarding permeability – the perm number is meaningless unless associated with a dimension – perms per inch, for example, would be standard. Yet when discussing insulation materials (foam), you are talking many inches, so how does that relate to the original perm number for one inch of material? I believe several inches of open cell spray foam will act significantly different from several inches of closed cell spray foam when it comes to permeability, but all working to decrease permeance as thickness increases.

Debra M.:

Debra M.: Thanks! I didn’t get into the airtight drywall approach to air sealing here, but in a cold climate, that would be the way to go.

Bob: Spray foam is one way to deal with the air sealing.

Franklin M.: Ah, yes, building inspectors. I didn’t mention their role in all this in the article, but building codes are coming along gradually and getting the message. Until they all get it, you just have to do what they say and try to do it ways that won’t cause problems. Putting plastic on the inside of a wall in a cold climate isn’t a bad thing. It’s just not a guarantee that you’re going to solve moisture problems. Putting plastic over closed cell spray foam is redundant and superfluous as well. Putting plastic on the interior side of a wall down here in Georgia or North Carolina is a recipe for failure.

Charles:

Charles: Good point about the retarder vs. barrier confusion. I was relying on people to remember what I wrote in the article on vapor retarders, but I’ll go back and edit the article to make it clear. Thanks!

Yes, there’s a lot of confusion about the difference between permeability and permeance. I discussed that in the other article, too, and pointed out that permeability is like density and permeance is like weight.

Good points as always. Vapor

Good points as always. Vapor retarders seem to me to be a backup in cold climates for poor air sealing, if they even work at all. It is amazing how things like vapor retarders, along with similar things like roof and crawlspace ventilation, get put in codes and never get reconsidered or revised. Hopefully increased requirements and testing for air sealing will lead to tighter homes and less vapor movement through convection in and out of buildings.

I remember in the 1980’s there was a big push to install polyethylene barriers on framed walls before the drywall. Once company would charge you to do this and guarantee the energy savings. I never went that route as a contractor I did plenty of what I now know to be stupid things that did plenty of damage to homes I was building or renovating.

Never personally saw one of the those poly sealed buildings after they tore open the walls to fix all the rot but I sure would like to.

Allison, thank you for your

Allison, thank you for your usual direct, clarity on this topic. We still find so many people insisting on using plastic layers in their wall assemblies but I really think most of these layers end up with penetrations over time and negate their purpose. The plastic then becomes more of a problem than a solution.

Come back and visit us again at the BSDG!

Sorry that I missed you in

Sorry that I missed you in Maine, Allison.

My concerns with the air-tight drywall approach is that drying framing members and potential intentional holes made by the occupants, a carpenter ant or mouse, or an electrician adding an outlet; could severely compromise the vapor retarding ability of the system with no easy way that I can think of to correct such compromises. After a house has aged for a few decades, I am sure that some compromising of the air-tight drywall system will have occurred.

As I have been promoting and building “double-wall” construction for 30 years and building only double-walls for the last 15 years, I believe that I have developed a unique approach that helps to eliminate all of the negatives. I install my vapor barrier in the middle of the wall system between the two walls. Such a location works both as a vapor barrier as well as an air barrier and eliminates the need for an external air barrier (not a easy application on a multi-storried building) as well as any special electrical pans and their sealing. The few holes in this barrier required for exterior lights/switches can be easily sealed with a can of foam or silicone mushroomed on both sides of the vapor barrier.

To thwart the comments of the expense of the double-wall headed my way, I would like to add that the second wall that I add to the interior is totally non-structural (24″ O.C.) and has less integrity than an interior partition wall. Its only job is to provide a chase for electrical, support window and door trim, another 3.5″ of insulation, and 5/8″ of sheetrock (part of the building’s thermal mass). This is off-set by no labor or materials for an external air barrier; no electrical pans, sealing, and their labor; no airtight drywall sealers and their labor; no special vapor barrier paint; a much less costly heating/cooling system; and much lower heating cooling bills. Yes, your window & door jambs are deeper (wider), but this only really adds to materials costs, and the application to install the vapor/air barrier is a bit more involved. You do need an air-to-air heat exchanger, but any tight building needs this regardless of the wall’s thickness. Fire away, I am sure that there are some additional concerns that I have not addressed.

G. Curmudgeon

G. Curmudgeon: Hooray for the statute of limitations, right? I’m sure there were some nice (aka nasty) photos to be had when they opened those walls.

Steve K.: I’d love to come back and participate in one of your regular Building Science Discussion Group meetings! I’ll be heading your way at the end of this month for Building Science Summer Camp but won’t catch your meeting then.

Thomas P.: Good point about the integrity of the airtight drywall approach. A double-wall construction would solve that problem and reduce thermal bridging, too. In my more general article on vapor retarders, I linked to a Joe Lstiburek article that gave a lot of different ways of dealing with moisture management, some of which had the vapor retarder in the middle.

Is this your opinion or did

Is this your opinion or did you perform tests to prove your statements. I would like to see some evidence. Please

Thanks for the article

So can I insulate the walls

So can I insulate the walls of my

existing home (built in 1956) with cellulose and not be concerned about whether or not there’s a vapor barrier?

Terry: It

Terry: It depends. If you’re in a really cold climate, maybe not. It also depends on the other components of your wall assembly. Many older homes have had cellulose insulation put in the walls without a problem, though.

Building codes must be based

Building codes must be based on personal opinions.One or two years do it this way then no no no we “learned” THIS is the way you really really do it.