The Fundamentals of Heating and Cooling Degree Days, Part 1

Let’s say you did some work on your home to make it more energy efficient – air sealing, more attic insulation, and a duct system retrofit. You’ve got your energy bills for 12 months before and 12 months after you did the work, and now you want to see how much energy you saved. So you sit down with all 24 months worth of utility bills, convert everything to a common unit if you use more than one type of fuel, and take a look at the numbers. Unless, however, you take into account another important factor, you may be led to incorrect conclusions.

You can’t simply compare the total amount of energy you used in the year before and the year after you made the energy improvements. As it turns out, weather changes from year to year, so an abnormally warm winter before the improvements followed by a really cold winter after the work might cause your home to use even more energy than before. But if you adjust for the difference in weather, you should be able to see the effects of the increased energy efficiency.

That’s where heating degree days and, to a lesser extent, cooling degree days come in.

What is a degree day?

A degree day is a combination of time and temperature difference (ΔT). The basic idea behind it is to give you an indication of how much heating or cooling a building might need. Emphasis on the “might” there. Degree days are just an estimate of heating and cooling needs, and we’ll look at some of the reasons why you need to keep them in the proper perspective.

A good starting place is the simplified† equation for heat flow shown below.

Now, this equation actually gives you the rate of heat flow. In the Imperial system of units that we use here in the US, the result will be in BTU/hour. So if we multiply that rate by the amount of time, as shown in the second equation, we end up with the quanitity of heat flow in BTU:

Yeah, I know both equations here use the same variable, Q, for rate of heat flow and quantity of heat flow. The first equation will usually have a dot over the Q in physics or engineering books, but let’s gloss over that and get to the main point here.

If we take the (ΔT x t) factor at the end of the second equation and use an appropriate base temperature, we can call the combination degree days. For example, in the US we typically use a base temperature of 65° F when calculating heating degree days. (More about that in part 2 of this series on degree days.) If the temperature stays constant at 64° F for one full day, that would give us one heating degree day (HDD). If the temperature is 60° F for a full day, we get 5 HDD.

Got it? It’s just the difference between the outdoor temperature and the base temperature multiplied by the time it’s at that temperature. Many sources of degree days use the mean daily temperature. Instead of being a constant 64° F or 60° F above, you get the same result if the mean temperature for a day is 64° F or 60° F.

Using mean hourly temperatures would be a better approach. Using mean minutely (is that a word?) temperatures would get you even closer. (If you’ve had some calculus, you know where this is headed, right?) The smaller you can make those time intervals, the more accurate will be your result for degree days. (OK, calculus lovers, we’re not going all the way there. Sorry. It is left as an exercise for the reader to do a Riemann sum with your temperature data and limit the size of the intervals to zero yourself.)

When we combine ΔT and t like that, we can substitute degree days (either HDD, CDD, or total DD) into the equation. Since it’s used more often, let’s look at it for heating degree days:

This is the form of the equation I used in my recent article on the diminishing returns of adding more insulation.

What are degree days good for?

I’ve already mentioned one of the uses of degree days, but let’s go ahead and make a list here.

- Normalizing energy use for changes in weather. This is what I referred to above and will illustrate below. If you make energy improvements to your home, degree days help you discover the real effect of the improvements.

- Comparing one climate to another. Degree days are one important measure. Design temperatures are another.

- Comparing the energy efficiency of one home to another home in a different climate. Just as you can normalize to weather changes in one location, you can get a feel for differences in the energy efficiency of homes in different climates.

Once we go through the example in the section on using degree days, I think you’ll see

Finding degree days

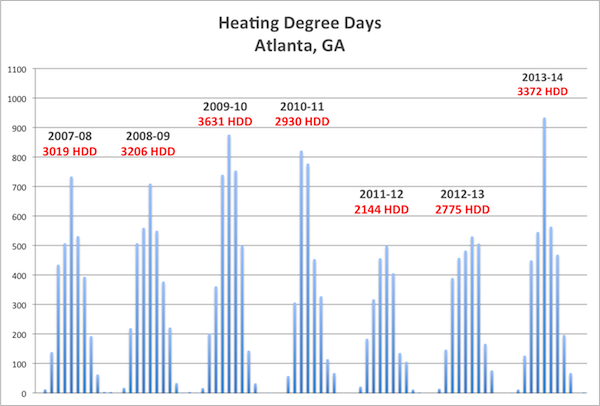

My favorite site for generating degree days is DegreeDays.net. It allows you to generate degree days for whatever base temperature you want to use. (See discussion of that in part 2 of this series.) I’ve been tracking heating degree days for Atlanta with data from DegreeDays.net for the previous seven years, and here’s my graph:

You can find degree days in other places as well.The Weather Underground website has tons of weather data, including degree days. Go to their page called Historical Weather and enter your location and the date. Once you get the data, you can select different time frames to see more than one day at a time.

I prefer DegreeDays.net because they base their calculations on more than just the average daily temperature. (I’ll explain in part 2.) It’s also easier to get what you want if what you want is degree days.

Using degree days

Let’s say that hypothetical home of yours is in Atlanta, and you did the work in the summer of 2013. Then you download my spreadsheet and find your total energy usage for those two years. Let’s keep it simple here and just look at the effect on winter heating bills. Here are the numbers for November through March of the pre- and post-improvement years:

| Year | kWh |

| 2012-13 | 43,328 kWh |

| 2013-14 | 40,987 kWh |

The reduction in energy consumption is the difference between the two numbers, or 2,341 kWh. At $0.12/kWh, the savings amounts to about $281 per year. Actually, it’s even worse than it first appears because a good chunk of those kilowatt-hours were actually from the natural gas used, and gas is really cheap these days. That’ll push the annual savings down below $200, making the return-on-investment not so appealing. (Of course, the actual ROI includes more than a financial return. With a good home performance retrofit, your home is more comfortable and healthful, too.)

We still need to account for the change in weather from one year to the next, though. If we expand the table to include heating degree days and some calculations based on it, we get this:

| Year | kWh | % Change | HDD | kWh/HDD | % Change | Normalized kWh |

| 2012-13 | 43,328 | — | 2,775 | 15.61 | — | 46,518 |

| 2013-14 | 40,987 | -5.4% | 3,372 | 12.16 | -22.1% | 36,237 |

Here’s where the power of normalization shines. If you look just at the reduction in kilowatt-hours, it looks like a 5.4% reduction. When we normalize for the colder winter post-improvement, though, you can see that we really reduced the consumption by 22.1%.

The last column in the table above, Normalized kWh, comes from multiplying the kWh/HDD by the average number of HDD in a year. I used 2980 HDD for Atlanta.

That works in the other direction as well. If the post-improvement weather is milder than what you had before, you may think you got a bigger benefit than you really did if you look only at the change in consumption without normalizing to degree days.

It’s not a unit of time

One point of confusion for many people is that “degree days” sounds like a unit of time. It’s not. That’s why we can have 5 heating degree days in one day and well more than 365 degree days in a year. Atlanta, Georgia has about 3000 heating degree days each year (65° F base temperature).

One point of confusion for many people is that “degree days” sounds like a unit of time. It’s not. That’s why we can have 5 heating degree days in one day and well more than 365 degree days in a year. Atlanta, Georgia has about 3000 heating degree days each year (65° F base temperature).

It’s not a unit of time. It’s a combination of time and temperature: ΔT x t.

Complicating factors

In part 2, we’ll go further into the discussion of the base temperature and some other complicating factors. If you want to read ahead, check out the article, Degree Days – Handle with Care!, on the Energy Lens website.

Despite the complicating factors and limitations, degree days are quite a useful invention. Whether you’re a homeowner just trying to understand your energy bills or a home energy pro who wants to know everything, it can be helpful to understand how they’re calculated and what they do.

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard. He has a PhD in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

The Diminishing Returns of Adding More Insulation

What’s Your Energy Efficiency Number?

We Are the 99% — Design Temperatures & Oversized HVAC Systems

Photo of thermometer by Ryan Rigby from flickr.com, used under a Creative Commons license.

Footnote

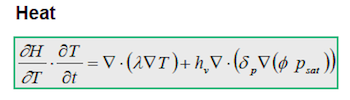

† To do heat flow right, you’ve got to use the full-blown partial differential equation (shown below) because the variables above actually vary over a smaller scale than a whole assembly. The hygrothermal modeling tool, WUFI, solves the full equation numerically and gives you a lot of power to manipulate the inputs…and a lot of opportunities to get screwy answers if you don’t know what you’re doing. The simplified form above is fine for a lot of things.

NOTE: Comments are closed.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Comments are closed.

Allison,

Allison,

How do you convert natural gas consumption to kWh before you add it to electricity? I tried to download your spreadsheet but wasn’t successfull. I try to avoid adding different source energies since the correct way from a home load perspective depends on relative heating and cooling equipment efficiencies.

Perhaps you will cover it in part 2, but one of the many issues in correlating energy use to degree-days is that there are a lot of energy loads in houses that are not related to heating and cooling and thus not related to weather either. I have done some degree-days analyses where I try to back out the “base” loads from cooling loads by subtracting our the average electrical loads during non-cooling months (spring and fall) from the cooling months, then normalizing the remaining cooling season consumption to cooling degree days. I do the same with heating loads using either natural gas or electricity depending on the heating system. I really don’t know if this works better, but it makes more sense to me.

Hello Mr. Bailes,

Hello Mr. Bailes,

Once again, it’s really hard to beat wikipedia: “Heating degree days are typical indicators of household energy consumption for space heating. The air temperature in a building is on average 2°C to 3°C higher than that of the air outside. A temperature of 18°C indoors corresponds to an outside temperature of about 15.5°C. If the air temperature outside is 1 °C below 15.5°C, then heating is required to maintain a temperature of about 18°C. If the outside temperature is 1 °C below the average temperature it is accounted as 1 degree-day. The sum of the degree days over periods such as a month or an entire heating season is used in calculating the amount of heating required for a building. Degree Days are also used to estimate air conditioning usage during the warm season.”

Since you are attempting to describe the Engineering of a Building, please re-address your heat equations for the opposite viewpoint of heat flow found in engineering vs science. Also, please describe from a heating oil co. POV. TY!

Great article. Looking

Great article. Looking forward to read part 2!