Fiberglass Is Still the Number One Insulation for Home Builders

The Home Innovation Research Labs (HIRL) does an annual survey of home builders to find out what they’re doing. The results of their 2019 survey of the homes built in 2018 are out now, and they recently published an interesting article about the breakdown of different insulation materials used by home builders. Before we talk about the implications, let’s see what they found.

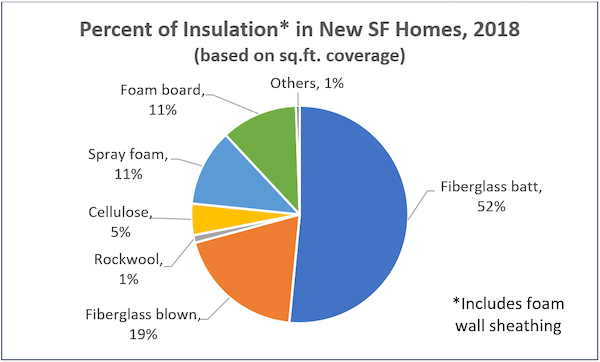

Here’s the pie chart of different insulation materials builders are putting into single family homes. (The SF in the title below stands for “single family.”)

As you can see, fiberglass is the dominant insulation material. 71% of all the insulation used by the 1,600 builders surveyed is fiberglass, 52% of it in the form of batts and 19% blown. According to the article, fiberglass has held fairly steady at that level for the past few years.

Since this material makes up more than two thirds of the insulation market for new, single family homes, this is a good time to review the problems, myths, and best practices associated with fiberglass.

Problems with fiberglass insulation

There’s really only one problem with fiberglass: poor installation. OK, it also can be really itchy if you get it on your skin and it’s a lung irritant if you’re working with it and not wearing a mask or respirator. So wear proper protective gear when you’re installing it or crawling around in a space where it’s exposed.

But the installation problem is well documented here and many other places. Since 2006, there’s been an insulation installation grading protocol, with grade 1 being the best and grade 3 being the worst. What I’d like to see HIRL add to their survey is how much of all that fiberglass installed each year is installed to grade 1, how much to grade 2, and how much to grade 3. Most of it, however, never gets assigned a grade because that’s not required for the typical insulation inspection.

So what’s the effect of grade 3? If you insulate a standard 2×4 wall with fiberglass, the average R-value drops about 12% when you install to grade 3 compared to installing it to grade 1. Yeah, when you go from R-11.8 to R-10.3, you still have a much better wall than older homes with no insulation in the walls, which would be about R-3.7 due to the other materials in the wall. And you won’t see much of a hit from that on your monthly bills.

But those little bits add up. Grade 3 insulation installations can cost thousands of dollars in heating and cooling costs and put a lot of extra carbon into the atmosphere over the life of the home. And for a lot of that insulation, you get one chance to do it right before the house gets remodeled or torn down.

Myths about fiberglass insulation

I love a good myth as much as anyone, and there are some doozies out there in the world of fiberglass. Here’s my number one all-time favorite:

Myth: Fiberglass-insulated homes are too leaky, resulting in high energy bills and comfort problems.

Whoa, there! Yes, fiberglass is an air-permeable insulation and many houses where it’s been installed are definitely too leaky. But this is like blaming your stale, moldy candy bar on the ingredients rather than the fact that the one you bought came wrapped in tissue paper.

A properly designed and installed building enclosure needs to have well thought-out control layers for heat, air, and moisture. Fiberglass is a perfectly fine control layer for heat, but it’s not going to stop air movement. That’s the job of the air barrier. You need both.

Myth: Fiberglass insulation causes cancer.

In the late 1980s, the National Toxicology Program and the state of California declared fiberglass insulation a possible carcinogen. That was based on early studies that later were shown not to be accurate. In 2011, both removed fiberglass insulation from their lists. Read more about it in this National Insulation Association article.

Oh, by the way, fiberglass is second only to cork as a healthy insulation material. See the table in Lloyd Alter’s article on the HIRL survey to see how it ranks.

Myth: Blown fiberglass attic insulation loses half its R-value because of convective loops.

I heard this one for many years before I finally wrote about it. Yes, there was a study from the early 1990s that showed blown fiberglass in attics could lose 50% of its R-value when the attic temperature dropped. The problem was the way the insulation was made, and the fiberglass industry fixed the problem. See my article for more details.

Myth: Compression in fiberglass insulation is a bad thing.

This is another persistent one, and I have to admit that I fell for it for a while, too. The truth is that compressed insulation does have a lower R-value than that same insulation expanded to its full thickness. Here’s what I wrote in my article on this topic in 2017:

Compression isn’t the problem. Incompletely filled cavities are a problem. Gaps are a problem. But you can compress fiberglass insulation as much as you want. The North American Insulation Manufacturers Association (NAIMA) has a little two-page document about compressing fiberglass insulation (pdf). Here’s what they say:

“When you compress fiber glass batt insulation, the R-value per inch goes up, but the overall R-value goes down because you have less inches or thickness of insulation.”

As long as you’re filling the cavity and getting the R-value you want, compression doesn’t matter.

Best practices for fiberglass insulation

If you have any say in the design or installation of the insulation in your home, here’s a bit of guidance for you. I’m focusing on fiberglass here but the same things apply to most of the alternatives, too. I’ll break it down by what kind of assembly is being insulated, starting at the bottom.

Floors

- Don’t use fiberglass batts to insulate most floors. It’s practically impossible to get a grade 1 installation with them. If the floor joists are open to below (as over a crawl space), move the building enclosure to the walls and ground/slab by encapsulating the crawl space or use spray foam, which won’t fall down.

- If you’re insulating a floor over a garage or over outdoor air and the cavities will be completely closed, fill the cavities with blown fiberglass.

- If there are relatively few obstructions in the cavities and the joists are dimensional lumber rather than I-joists or open-web trusses, batts can work. Again, it’s best to fill the whole cavity.

- If you do use batts to insulate floors that are open on the bottom, make sure they are in contact with the subfloor at the top of the cavity and as secure as possible. You’ll also need to check them regularly because of this thing called gravity.

Walls

- Both batts and blown can work fine if you fill the cavity completely.

- With batts, cut around junction boxes and put the cut-out piece behind the box.

- Split batts around wires.

- Cut batts around pipes, blocking, and other obstructions.

- Use unfaced batts whenever possible. They’re easier to install properly as well as easier to inspect.

- Put an air barrier on the attic-side of kneewalls. (Or eliminate kneewalls by encapsulating the attic.)

Ceilings

- Blown insulation is better for filling the joist cavities.

- When installing batts, follow the guidance above for walls when it comes to fitting the batts in the joist cavities.

- Choose batts that are the same thickness as the depth of the joist cavities. To get more R-value, add another layer of batts, running them perpendicular to the joists, or blow insulation on top. (There’s a reason most attics have all blown insulation, not batts or a combination of batts and blown.)

- Make sure the blown insulation reaches the minimum thickness necessary for the design R-value. Some contractors like to deliver average thickness, but that can result in significant under-performance of your insulation, as I described way back in 2010 when I wrote, Flat or Lumpy – How Would You Like Your Insulation?

The big takeaway

I’ve written many articles about insulation, a lot of them about fiberglass or applicable to fiberglass. The most important thing I want you to take away from this article today is that you need to understand fiberglass — or any insulation material, really — to get the most out of it. As I wrote above, the main problem is poor installation. Learn the truth behind the myths so you can dismiss them. And then follow the best practices I outlined.

Fiberglass is a perfectly fine insulation material with a bad rap because of all the sins committed — or said to be committed — in its name. Learn the truth, do it right, and you’ll be healthy, wealthy, and comfortable…or at least a bit closer!

Related Articles

How to Grade the Installation Quality of Insulation

Flat or Lumpy – How Would You Like Your Insulation?

2 Ways to Get the Best Insulation in Your Home

The Layers and Pathways of Heat Flow in Buildings

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 10 Comments

Comments are closed.

When I used to work in home

When I used to work in home construction, I always dreaded installing fiberglass batts. I would itch for a week afterwards. We always used unfaced batts. I wondered why paper-faced and foil-faced fiberglass even existed. My conclusion was so that installers could avoid touching the fiberglass, which is why it rarely gets installed properly. But why foil-faced? Is that supposed to be a radiant barrier? A vapor barrier? I don’t thinks so.

I’m one of those few that

I’m one of those few that believes that all conditioned spaces above garages need to be insulated with 2″ ccSF applied under the floor decking, and the remainder, with blown insulation. The reason is to stop any moisture and chemicals moving from the garage to the habitable space.

What happens next? Foam,

What happens next? Foam, cellulose, or fiberglass…attics, walls, or crawl spaces…rodents happen next! Their job is to explore. Despite the insulation industry’s fix of the convective looping issue, rodents make a labyrinth of thumb-sized to wrist-sized trails and tunnels (air passageways) throughout any type of insulation. Actually, it’s kind of cute seeing how the little critters have busily swept their tunnels clear of mouse-mouthful-sized bits of expanding foam onto the crawl space floor. However, what impact is that having on insulation performance? Even more important…what is the impact on occupant health with their deposits of (smelly) urine, feces, hair, nesting material, and…(sadly)…dead mouse bodies. Even more important yet… every so often in the rodent community a wire-chewer comes along. Now we have exposed electrical wiring going undiscovered. The takeaway… after project completion, immediately begin the regimen of house monitor/maintenance. After all, its been said that “Mice often make astray the best laid plans of men and women.” …or something like that.

Rick, You are the first

Rick, You are the first person I’ve read to comment about rodents ,ever, besides me. I’ve never opened a wall without finding some evidence of them. I believe that fiberglass is their favorite material, and I’ve found stud bays that had no fiberglass even left after they had stripped it for nest building. They are just as much of a problem in motor vehicles. A buddy of mine had to replace his truck transmission after rodents packed it with debris. I have endless stories. But builders don’t pay any mind. Their minds are filled with the details of intricate building plans and systems which they must obsessively watch for quality. Yet this perfection goes right out the window if the details do not include very robust protection against rodent invasion.

Rodents work for daily survival. They don’t live long, so they work fast and leave lots of offspring to inherit and expand their efforts.

And it was Scottish poet Robert Burns who wrote (in translation) “the best laid plans of mice and men off-times go astray.” I would say that mice don’t plan much, they act on instinct. It’s humans who have the grand designs, and forget about mice.

Good read. The key point made

Good read. The key point made is that fiberglass insulation does not stop air flow. It is for conduction not convection. A tighter house with poor insulation is still better than a lot of insulation but air leaks. Convection always over-rides conduction every time. The homes that I build get blower door tests of .36 ACH50 consistently.

Thomas, I think you should

Thomas, I think you should distinguish between convection and air infiltration/exfiltration. If I’m not mistaken, the later happens due to pressure differences, but the former does not, at least not significant differences. Fiberglass can’t stop air moving under pressure, but does a good job of stopping convection.

Thomas,

Thomas,

That doesn’t mean you can’t have both a tight house and use fiberglass. I have dense pack fiberglass in my walls but my house came in around .2 ACH @50 Pascals.

The only cavity insulation that acts as both an air barrier and insulation is spray foam. I’d take dense pack fiberglass over spray foam every time for new construction (except for raised floors and vaulted ceilings perhaps).

@Allison, I’m surprised you

@Allison, I’m surprised you didn’t differentiate between batts and blown-in fiberglass for walls. In my experience, it’s a lot easier to get to Grade 1 with blown-in. In fact, I can probably count on my fingers the number of true Grade 1 installations I’ve seen with batts. Yes it can be done, but good luck finding a crew that can do it.

Blown-in (typically done with netting) costs a bit more, but you can get to R-23 in a 2×6 wall, which you can’t do with batts.

The mentioning about resents

The mentioning about resents is just an example to illustrate another important aspect of sustainability. Now that folks are occupying and using the completed Sustainable building, the time to manage the “what happens next” part of it becomes of critical importance. You can’t stop a green bananna from turning brown, and , long term, you can’t stop a green building from going brown either. We’re just asking Nature to slow down the building decay process a bit until we’ve decided we’re totally finished with it. Our maintenance plans should be just as broad-focused and detailed as our Sustainable building planning and construction process was. Otherwise building performance will fall apart sooner rather than later.

Good article and explanation

Good article and explanation of why the myths are really myths. I remember back in the day also being under the assumption that you would not want too much compression in fiberglass. It is all about the gaps and the R-value!