Roof Overhangs and Moisture Problems

Roof overhangs and moisture problems in the walls of a house ought to be related, right? After all, most of the water that lands on a house hits the roof first. From there, rainwater runs to the bottom edge of the roof and then makes its way to the ground. (I’m assuming a sloped roof.) Gravity may be the weakest of the fundamental forces, but it dominates with the flow of bulk rainwater hitting the top of a house.

I did a little survey on LinkedIn recently to see how people think of this issue. You can see the screenshot of my question and the results below.

80 percent of the people who answered think deeper overhangs significantly reduce the chances of moisture problems. Are they right? Let’s look at the results of a more formal study.

A study from British Columbia

In the 1990s, an interesting study came out of western Canada. Titled, Survey of Building Envelope Failures in the Coastal Climate of British Columbia (pdf), they did a survey of 46 low-rise residential buildings. 37 of those buildings had moisture-related building enclosure failures. They looked at several factors related to the problems, including:

-

Overhang depth

-

Cladding type

-

Drainage plane type

-

Sheathing type

-

Insulation type

-

Orientation

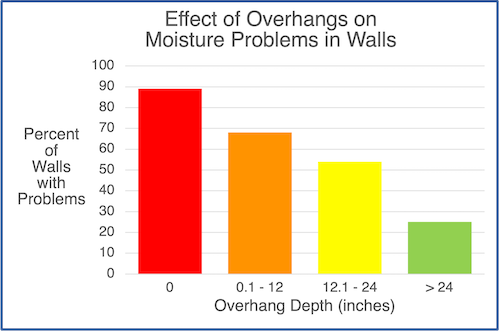

Among the 46 buildings, they studied 72 individual walls. What I found to be the most interesting part of their data was their correlation of the roof overhangs and moisture problems. The chart below shows the percentage of the 72 walls that had moisture problems relative to the depth of the roof overhang above the wall.

Conclusions from the BC study

At the end of the report, the authors list 12 conclusions. Here are what I consider to be the most important of them:

-

“Exterior water is the moisture source for by far the majority of the performance problems.”

-

“The vast majority of the problems ( 90% ) are related to interface details between wall components or at penetrations.”

-

“Exterior moisture penetration through or around windows is a significant contributor to moisture problems.”

-

“Buildings with roofs overhanging walls perform significantly better.” [Emphasis added.]

-

“In general, buildings with simple details…performed better.”

If I had written the report, I would have put more emphasis on the effect of overhangs than they did. They found that water from the outside caused far more problems than moisture from the inside. The best thing you can do to keep water off of walls is to extend the roof beyond the walls, and the farther the better. When you keep the water off the walls to begin with, the flashing, interface details, and penetrations through the wall don’t matter as much because they don’t see as much water.

It’s important to keep in mind that this study is from coastal British Columbia. Not only do they have a high amount of rainfall (up to 160 inches per year in some places), but the cool weather reduces drying potential for building materials that get wet. In other climates,the results may be different. Also, it is possible to have no roof overhangs and avoid problems by making sure the water management details are designed and installed properly with appropriate materials.

Down and out is the rule for water management

Let’s finish up with a quick review of good water management principles. You want to keep rainwater moving down and out. Overhangs help because they move the water out before it goes down. If the house has no gutters, the water will hit the ground some distance from the house. Then you need a slope in the yard to keep the water moving away. With gutters, the water gets channeled down to the base of the house. Again, you need slope or downspout extenders or both to keep the water away from the foundation.

For water that does hit the wall, this diagram from Building Science Corporation shows the principle of keeping the water moving down and out. Also see the article Rain Control in Buildings by Professor John Straube for more good recommendations.

![Down and out is the rule for water management [Image courtesy of Joseph Lstiburek]](https://www.energyvanguard.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/proper-layering-drainage-plane-flashing-bsc-small.jpg)

Failing to control the water

When you don’t have overhangs or good down-and-out water management, bad things happen. I saw the house below near our office a couple of years ago, and you can see they had serious water damage. The large damaged area in the middle (to the right of the window on the left) happened because a lot of water came off the roof in that location.

Not only did that area get the water from the section of roof straight above, but the small gable over the right-side window channeled more water to that location. Without an overhang to move water out and then down, all that water went straight down the front of this house. Poor water management behind the siding led to these problems.

The window on the right was spared the massive downfall from the roof because of the gable. But with no overhang, it got more wind-driven rain. This wall faced west, the direction a lot of storms come from in Atlanta, so it does have moisture damage beneath the window. The damage on the right side also may have been aided by condensate from the window air conditioner.

In short, the depth of roof overhangs and moisture problems are related. Deeper overhangs mean you don’t have to depend as much on the water management details having been designed and installed perfectly.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

Air Barriers, Vapor Barriers, and Drainage Planes Do Different Jobs

Professor John Straube on Moisture Physics

The Drainage Plane Flashing Battle Continues

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 26 Comments

Comments are closed.

I have large overhangs on my limestone block home. Very rarely do the walls get wet, but I have a different problem. Any ideas on how to keep mold/mildew from growing underneath?

For the most part, I can’t complain as I believe the 50 year old soffits are original. The fully covered birth facing porch and connected overhangs do seem to have more issues that other areas. Is this just a tradeoff? Or is there something you think I can do to help reduce this?

Finally – thank you for your blog! As a nerdy homeowner, I love it.

Josh: I’m not a stone expert, but maybe someone reading this will be. They’ll need more information, though. What does “underneath” mean? The whole wall? Just at the bottom? What climate are you in? What makes you think it’s mold/mildew and not algae or something else?

Thanks for the kind words!

I suppose it could be algae as well. The walls themselves are actually fine, it’s the underside of the soffits where I see this happening. Currently my home has wood soffits. They are three foot overhangs with quite a bit of venting. At some point in the future, I’m looking to move to a non-maintenance product (metal, vinyl, Masonite). Biggest issue on that is figuring out something aesthetically pleasing – 3 foot overhangs are no the norm, so I don’t know how many options I’ll have.

The stone stays clean because of the protection from the overhangs. There are a few spots (kickout knee wall, mailbox) that are exposed to the elements where the stone grows things (moss, lichens, algae, etc).

I’m in northern Illinois, so we get it all.

The comment on shading and cooling is very true. I believe my home was designed with that in mind as it is a sprawling ranch. It’s got a large southern exposure that brings in lots of natural light and in the winter, heat from the lower sun. During the summer those big overhangs keep things much cooler. The home is also built around a large thermal mass (double stone fireplace) – so we do see some help from that in the milder weather. Works against us in the extremes I think, but I’m no expert.

It’s normal.

Dust and dirt act as a food source. Muggy humid summertime temps provide moisture.

Nice article Allison! We always try to encourage at least 18″ overhangs. And this helps to show that building a great home doesn’t have to be complicated if people follow a few basic rules.

That’s a good practice, Charles!

The angled board sheathing adds another interesting element. It can move the water laterally and it moves downward behind the siding. I was called to repair some rotting siding down near the foundation. Was initially puzzled as to where the water was getting in. Finally traced it to a small leak above a double window, just like in your picture. The damage ended up several feet over to the right of the window by following the angled sheathing downward.

Thomas: Yeah, those built-in water slides can share the love.

Most folks consider overhangs to be strictly an issue of style. Get over it!

I wanted a flat roof for my new home because it’s more efficient AND less expensive than pitched but I didn’t want to go with the classic Santa Fe style that has no overhangs (i.e., roof parapets are simply extensions of the walls). So created my own style: a flat roof with overhangs!

Overhangs not only mitigate against bulk moisture problems but reduce exterior maintenance and most importantly in cooling climates, provide shading. Who wouldn’t want all that?! There’s a big difference between designing a house and then trying to make it high performance, and designing a house from the ground up to be a high performance!

David: Thanks for bringing up the shading aspect. I meant to mention that in the article.

Interesting about moisture. Too bad that the fire danger of overhangs is high. There’s always something.

John M6: I don’t think it’s the overhangs that increase the risk of fire. It’s soffit vents that pull embers from nearby fires (wild or otherwise) into the attic. Because the problem has been increasing, there are now fire-resistant vents available.

After looking at building moisture problems for fifty years in the Colorado Climate it is not unusual for the overhang or lack thereof to contribute to moisture problems. The main culprit in our area is the lack of a defined down and out criteria in building construction enforcement. The ICC contains many ways to control moisture infiltration at the roof to wall interface and similar to BC the problems we observe are from Ice Build-up during the winter. The failure to install a ice and water shield barrier that extends up the roof 24 inches or more inside the exterior wall plane creates a source of moisture entering the building envelope. In commercial building roof drainage is a major problem in moisture entering the building due to poor control and discharge areas for moisture.

Hi Allison,

We called this the leaky condo crisis and the assumption was EIFS failure, or the incompatibility of that system for the rain-soaked wet coast.

I have a product called “Rainhandler” (https://www.rainhandler.com/) installed on my home in place of traditional gutters. It works remarkably well. I have a 12″ overhang and there seems to be no issues with the exterior walls having moisture problems. This product eliminates the need for clogged gutters and the traditional issues with the runoff from the downspouts. Allison, you may want to review this product and possibly write an article about it. Thanks for your blog.

Dennis

While I’ve seen Rainhandler at work and they can get the water bit further away from the building IN A GOOD RAIN. However they don’t address the problem of too much water too close to the foundation. Unless that is addressed with drainage or grading (or both) their use can lead to large water flows toward and down the foundation and in the north inducing frost driven push forces on the foundation.

KUDOS once again, Allison! This is a superb summary of some of the key #BuildingScience principles that, if followed & properly implemented, will significantly reduce the chance of #Unhealthy #Moldy structures. U ROCK dude!

I think that we are overlooking another important conclusion of the BD study:

“In general, buildings with simple details…performed better.”

Architects like to add lots of roof gables and valleys and other details that just cost more money and are more difficult to get right. I am not saying that we should live in ugly boxes, but is it not possible to have simpler exterior envelopes that still look good?

Absolutely right, Roy. That one is at least as important as having overhangs.

In 36 years of architectural practice in Nova Scotia and Alberta I learned to carefully study the climate in the area for which I was designing. In Halifax the rain is horizontal. In Calgary it is rare, intense and strictly vertical. In Vancouver it is not as intense, but hangs around for weeks. Each requires a different design solution. All require overhangs, although in BC soffit venting has been known to allow moisture in to cause mould and rot. I gave up using gutters years ago in favour of carefully sloped grades because that is how some hundred year old buildings I restored handled the water.

Your article doesn’t mention prevailing winds as a factor but I would think the greater the typical windspeed the greater the water penetration in walls. The wall height also is a factor; bigger houses tend to have taller walls. Also in the intown Atlanta market the biggest issue I see is with the weather resistive barrier. While builders seem to be treating the large penetrations correctly (windows & doors) the multiple smaller penetrations for ducts, pipes and wiring are not sealed to the WRB. These penetrations are often cut through the cladding which is creating a future repair nightmare.

I will admit that overhangs look good and can provide useful shading, but exterior walls should be completely water proof from top to bottom by using appropriate drain planes and flashing. Relying on overhangs to prevent exterior moisture problems does not sound like good practice to me. They are just a band-aid when it comes to controlling moisture.

Apologizing to architects in advance, there is a whole village on the coast in California called Sea Ranch. You are forbidden from building a home there with overhangs. The result is a great market for contractors removing the siding, replacing the sheathing, and waiting not very long for the next call. When we were looking to buy a house in the area, some Sea Rance houses that we looked at had the contractor there as they were showing the house. Others I walked into, smelled the mold and left. We ended up buying a house with overhangs, 8 miles North, still on the ocean with wind driven rain. There was some sheathing damage on the ocean side, and we removed the siding, put in a drainage plane and yay, no surprise, it works great.

PS you pay a huge price premium when you buy a Sea Ranch house compared to other houses in the area.

I’ve been working in the Minnesota area for 50 years and have found the following as applies to Overhangs:

They can keep rain off the walls.

They can contribute to ice dams in ways that are not obvious.

They can contribute to mold and mildew growth.

They can be terrible to detail and get right.

Sometimes you just need to give up and cut them off.

To explain,

They can keep rain off the walls.

Yes, having a larger overhang can contribute to moving the water away from the walls. They will have varying degrees of success due to rain and wind direction. Overhangs are not a replacement for an excellently detailed and installed drainage plane.

They can contribute to ice dams in ways that are not obvious (I’m leaving off all discussion of classic Ice Dams in this. They happen, they are bad, and they are not the only way Ice Dams form.)

This is a tough concept that normally gets a lot of negative comments, people saying I’m wrong, etc… Large overhangs and ventilated eaves/roofs can actually increase Ice Dams. Here’s the physics. Anytime you have snow piled on the roof, especially the eave, it is extremely sensitive to 32Fdeg (or 0Cdeg). As soon as the snow layer reaches freezing and above, it’ll melt. With a Ventilated Roof, on a ‘warm’ winter day, you can actually be introducing above freezing air to the bottom of the roof sheathing; instant snow melt and freeze when the snow melts. Large(r) Overhangs can enhance this on the Sun Side of the home, because they can trap the warm air that naturally rises off the Sunlit wall and can direct it into the roof/attic through the same soffit vents put there to ventilate the roof; same result, instant snow melt and freeze when the temp drops. To a lesser degree we can have some seriously awful temperature changes here in Minnesota that can also have it ‘Snow’ or ‘Rain’ in an attic, but I’ll try to elaborate on those in a different thread.

They can contribute to mold and mildew growth.

As noted above in the comment about the stone house, Overhangs can facilitate Mold and Mildew growth. This is usually noticeable where the wall is basically totally shaded and also somewhat blocked from airflow. Moist stagnant air can collect below the eave, usually wetting the siding surface, which encourages a build up of both spores, and ‘dirt’. Organics + water+ food + temps = Mold/Mildew; simple biology.

They can be terrible to detail and get right.

Today’s design still is Gables, Gables and More Gables. All of that geometry has to connect somewhere and the overhangs, both Rakes and Eaves, have to work together. Kickout Flashings, Valleys, Gutters, etc all have to work in larger fashions as the sizes of the overhangs increase. The gables also mean greater concentrations of water as noted above in the very telling images of the 1930’s – 40’s Cape. Imagine 3 or 4 or more all concentrating water.

Sometimes you just need to give up and cut them off.

There have been homes where we trimmed rakes back to minimal to meet a ‘style’, and also to minimize some ot the issues above. It looked good (to our eye, and the customer), but we needed to really watch the detailing to make sure everything was ‘shingled’ and was ‘pushed out’ at every layer.

To sum up, I’m not against overhangs. I’m for them because of where we live, but like every part of Building Science, making one choice will always lead to needing to make several more.

“You’ve got to think about big things while you’re doing small things, so that all the small things go in the right direction.” Futurist Alvin Toffler

Don’t tuck your rain pants into your rain boots…

Not directly related to moisture, but wider overhangs also have another benefit: they provide shade in the summer (when sun is high in the sky) while not obstructing sun in the winter (when sun is low in the sky).