4 Ways to Fix Your Duct System

I’ve written a lot of articles about ducts here, but I haven’t yet addressed today’s topic: common problems with ducts and how to fix them. This one is for homeowners or renters who want to save money and be more comfortable. And the nice thing is, these are relatively easy things to fix if you’re a handy do-it-yourselfer. With the guidance I provide in this article, you can go into your attic, basement, or crawl space and spot the problem areas. And then you can fix your duct system.

The fundamentals of ducts for heating and cooling systems

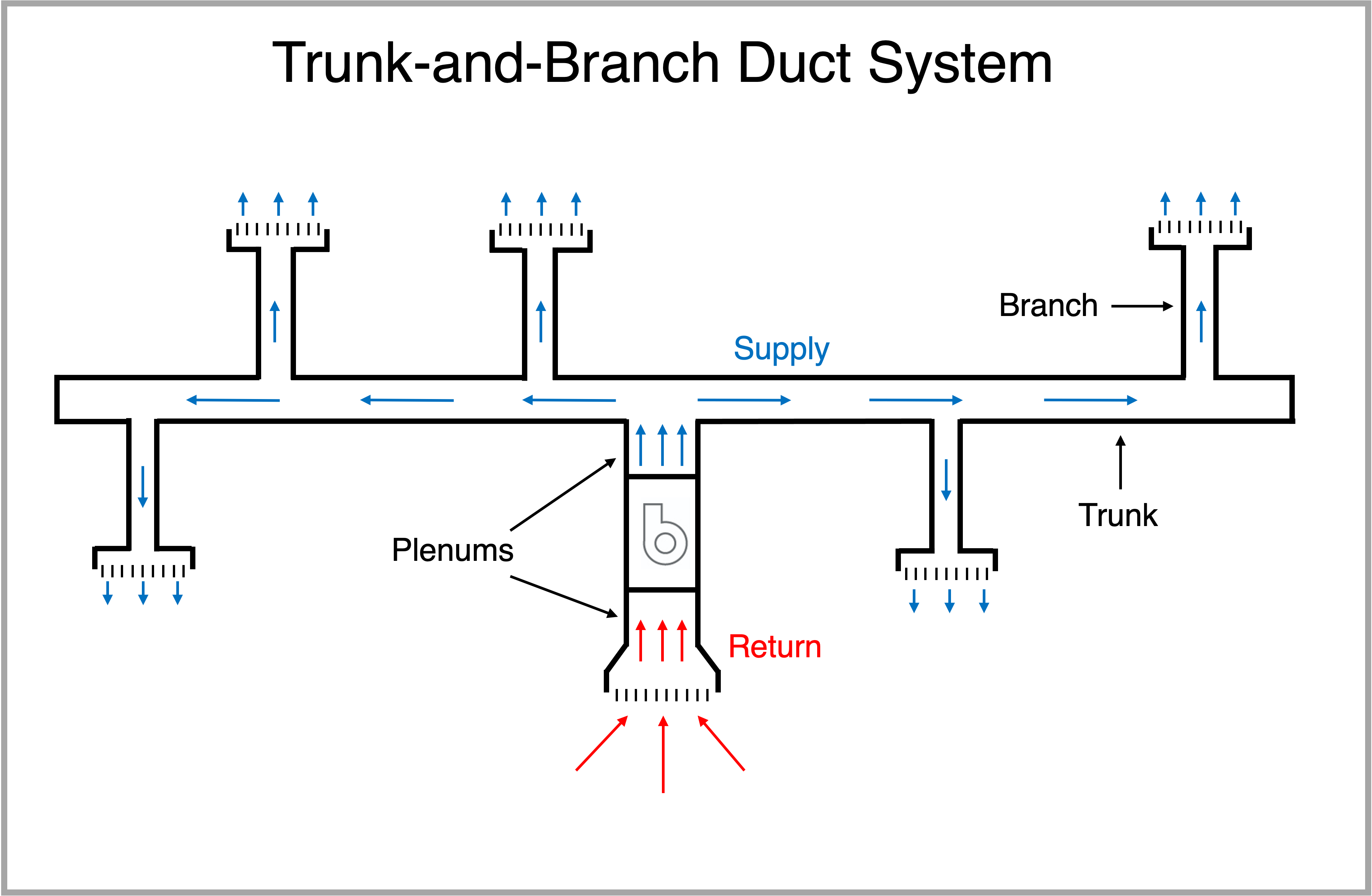

Before I dive into the problems and fixes, though, let’s review the fundamentals of heating and cooling with air. The heart of a forced-air heating and cooling system is the air handler. That’s where the air gets heated or cooled. It’s also where the blower is. It’s the fan that moves the air.

As with any other fan, air gets pulled in on one side and blown out the other. Unlike a box fan or a ceiling fan, though, the air is constrained to move through ducts. The ducts on the pulling-in side are called the return ducts. The larger piece of duct return duct connected to the air handler is the return plenum. The ducts on the blowing-out side are called the supply ducts, with a supply plenum connected to the air handler.

There are some important things to know about the air moving through the ducts. First, the pressures are highest near the air handler. That makes problems there more important than problems farther away. Second, the air on the return side is at room-temperature. That means insulation is more important on the supply side, where the air is significantly hotter or colder than room temperature. Third, ducts in unconditioned spaces—attics, basements, crawl spaces, or garages—are where you should focus your efforts since losses there matter more than losses in the conditioned space.

Got all that? OK, let’s dive in.

Disconnected ducts

This should be the first thing you look for. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen supply ducts blowing conditioned air into attics or crawl spaces and return ducts sucking superheated, freezing cold, or really humid air into the system. Heating systems and air conditioners work much better when they pull all the air from the house.

Sometimes the disconnected duct is obvious and can be seen from far away. I found the one below blowing cold air into a hot attic.

Other times, you have to get closer to the duct and maybe even move insulation to see the disconnect. They don’t always fall off completely or open giant fissures.

There’s another way you sometimes can find disconnected ducts, too. If a supply duct has come completely disconnected, the vent at the end of the duct won’t blow any air into the house. So make sure the system is on and check all your vents for air flow inside the house. That can give you an idea of where to look when you go into the attic, basement, crawl space, or garage.

Once you’ve found a disconnected duct, the fix involves putting them back together. But take a good look at the connection and try to understand why it fell apart. Often it’s because the two parts weren’t mechanically attached to each other well enough. You can’t rely on tape only to hold them together. Use zip ties, hose clamps, screws, or staples, depending on the type of duct. Then seal the connection with mastic (as shown above) or mastic tape. (See the resources at the end of the article for more detail.)

Excess duct length

This problem adds resistance to the duct system. Resistance in the ducts can reduce the air flow or cause your system to use more energy, depending on the type of motor turning the blower. Sometimes installers leave extra duct length to cut down on noise. Sometimes they just don’t want to make that extra cut.

In the photo above, the duct you see is maybe 10 or 12 feet long. But it has as much resistance as about 100 feet of properly installed duct. If you see something like that, disconnect the duct from one end, cut as much of the excess length off as you can, and reattach the duct with the inner liner pulled tight. (See the next section.)

Flex duct resistance

Removing excess duct length is an easy way to improve the air flow in your system, but resistance increases in flex ducts in other ways, too. In the photo below, the two flex ducts are poorly supported. Rather than being connected in a straight line between the two endpoints, they’re hung in a way that increases resistance to air flow. The inner liner isn’t pulled tight. They’re pinched a bit at the support. Air doesn’t really like roller coasters.

Ah, you can see another sign of a lazy installer in the photo below. “Hey, let’s just drape this duct over the collar tie in the attic. That’s good enough.” No, it’s not. Again, the duct’s inner liner isn’t pulled tight, and the duct is pinched right there.

One nice thing about flex duct is that it’s easy to work with. If you’re ever installed rigid ducts, you know what I mean. But that just makes it easier to abuse, too. When you see flex duct turning like the one in the photo below, you should immediately start looking for ways to reroute that duct.

The keys with flex duct are:

- To run it as straight as possible, and

- To pull the inner liner tight.

That’s how you reduce the resistance to air flow and fix your duct system.

The photo above shows a short section of flex duct I installed in my 2016 bathroom remodel. It wasn’t mechanically fastened on the left side yet, so the inner liner isn’t pulled as tight as it should be there. I did this just to take a photo of the inner liner, which is the important part for air flow. The plastic liner between adjacent pieces of the embedded helical wire should be as flat as possible. The right side of the duct is about how it should look when it’s installed.

If you have flex duct, these problems are pretty easy to find. Fixing them is all about finding ways to run them as straight and tight as possible.

Uninsulated or poorly insulated ducts and boots

When ducts are in unconditioned spaces, you don’t want them gaining much heat in summer or losing much heat in winter. That’s why we insulate them. But don’t just look from afar and be satisfied if you see insulation. Get in there and look at all the ducts. A little bit of uninsulated area can make a big difference. That’s as true for ducts as it is for attics.

The parts that always seem to be the worst for insulation are at the connections. The photo above shows a particularly bad butt joint. In this case, I’d redo that whole connection and make sure it’s connected, sealed and supported properly in addition to insulating it.

Another kind of connection that can make a big difference is where the duct connects to the boot (photo above). A duct boot is a sheet metal fitting with a duct connected on one side and a vent on the other. When it’s uninsulated in an unconditioned space, it can do more than just add or steal heat from the conditioned air. In a humid basement or crawl space, that uninsulated boot becomes a condensing surface. That water then can drip down into the duct and blow out the outer jacket on the duct, as you can see below.

The photo below shows a fully insulated duct boot. Note that the outer jacket is taped up to keep humid air from getting in and finding the cold boot in cooling season.

The key with uninsulated parts of a duct system is finding them and getting them insulated. But also, pay attention to what you’re insulating over. Sometimes it’s best to do some repairs and sealing before adding insulation.

Air flow and other considerations

Some of the fixes I suggest in this article can increase the air flow. Some can decrease it. When you reconnect disconnected ducts or seal the leaks in a duct system, the air flow can decrease. If you have natural draft combustion appliances, you should seek professional help to ensure you don’t make a change that causes backdrafting of those appliances. It’s usually a gas water heater, but others might be susceptible as well. Look for a professional with a certification through the Building Performance Institute (BPI) or some other credential for testing the combustion appliance zone (CAZ).

I’ve pointed out some of the biggest, ripest low-hanging fruit for how to fix your duct system. The fixes are within the realm of possibility for handy do-it-yourselfers, but beware that working in attics and crawl spaces isn’t for everyone. Also, I didn’t get into all the details of how to fix your duct system. The type of fix depends on the type and location of duct, so here are some good resources for more information:

- Building America Solutions Center resource guides on ducts – Lots of great info here

- Building Science Corporation duct sealing info sheet – Be sure to explore the site for their other helpful resources.

- Weatherization program Standard Work Specifications – See the relevant sections under heating & cooling.

Heating and cooling accounts for about half of the energy use in many existing homes. By addressing the problems I’ve shown above, you can reduce your energy use and make your home more comfortable. Even if you don’t fix your duct system yourself, if you find the problems, you can direct someone else to do the work.

Doing the kind of repairs I discussed here will improve your home a lot more than caulking the windows and weatherstripping the doors. Which is why I’ve said in the past, don’t caulk the windows.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He also has written a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

17 Steps to Better Duct Systems

7 Ways to Improve Ducts in an Unconditioned Attic

How to Install Flex Duct Properly

10 Uncommon Tips for Winterizing Your Home

Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 13 Comments

Comments are closed.

Another big mistake I see allot is hanging the ducts up as close to the roof deck as possible. That’s the absolute worst place to have your ducts. Attic temps increase allot going from the attic floor to the roof deck. They should be as low in the attic as possible and preferable buried in copious amounts of insulation.

Robert: Yes, I’ve seen that too many times, too. I wrote about it here:

Keep Out! – One Place NEVER to Put HVAC System Ducts

I decided not to include that in this article, though, because it’s harder to fix. But it’s definitely a problem. And it’s even harder to fix when the duct is trapped in a cathedral ceiling.

Yep. My townhouse is like that. All of the ducts are sandwiched between the roof deck and cathedral ceiling and then snake down between the studs of exterior walls to reach ground floor ceiling. I’m sure some of them have puncture marks from the re-roof a couple of years ago.

For 20 years I’ve been praying that house would get struck by lightning or have a huge tree fall on it.

yes sir! See ducts all the time next to the roof deck. In many cases the duct works have holes in them from the roofing nails. Can you say leaky ducts!

I have often had people asking me whether to spend X thousand extra to go to a higher SEER system. The blanket answer is no. If you want to spend X thousand dollars on your HVAC system, spend it on duct sealing and insulation. This money is way better spent. I like to show the heat gain of duct in an attic versus the house heat gain of the attic. The difference in 2000 square feet of R-30 attic versus 400 square feet of R-4 duct is eye opening.

Lee: Hear, hear! There are definitely better ways to spend your money, and fixing duct problems is one of the best.

What about the lifetime of flex duct? It’s not built to last anywhere near the lifetime of hard duct material, so is it better to just plan to replace it (by a competent, diligent contractor) than repair it? And what to do with sheet pan ductwork between floor joists?

David: Both good questions. Yes, before cutting a piece of flex to shorten and tighten it, it’s a good idea to check its condition. Replacing it with a new piece of flex will be harder—sometimes much harder—than just dealing with one end, so that might push it out of the DIY category for some people and in some situations.

Regarding panned joist returns, I didn’t mention that one because doing it properly would be beyond DIY skill level in my opinion. But of course, they could slather mastic all over the outside and get it as sealed up as possible.

Ok, then a follow-on question: Would it make more sense to replace end-of-life flex duct (assume EOL is around the warranty length) that was installed in a schetchy way with interior hard ducting (i.e., like new construction) rather than either fixing the old (and possibly have it fail shortly after) or tearing out the old flex duct and installing new?

Allison, great article. I have HVAC (gas) system installed in a crawl space vented attic here in DC area. The space is so tight that it is a challenge to check the the flex ducts for integrity. One thing HVAC guys suggested is to spray foam under decking of the roof in the attic wherever it can be reached with 3” open cell foam to reduce the summer heat temperature. Leave the attic vented with baffles and ridge vented. Can you comment on this idea or write an article? I thought the moisture might be a problem, but the HVAC guy pointed out that the attic would stay vented. Thanks!

You had me at DIY. My house has a vented attic in southern CA. Looking at my R4.2 insulated (black color) flex ducts, that also sometimes have mastic over the insulation (not under) connecting it to the plenum and leaking noticeable amounts of air at the connection , I am thinking to get rid of some duct insulation , fix the connections, seal, and reinsulate ducts with better insulation (and not black), even if just part of the duct runs (and leave the rest at R4.2)

Thoughts ? Suggestions ?

Take the time to look up the proper way to use tape and tie straps when making your connections. There is a proper series of steps to be done properly. Not all duct tape is the same and codes specify which should be used and where. The inner flex especially needs to be both taped and strapped. The outer insulation layer needs to be tucked back inside itself with no insulation showing and then strapped tightly. Good trade craft will make you proud.

Allison,

On a frequent visitor to the vanguard website. About a year ago I had a Daikin inverter with 3 zones installed in my house. Today I noticed that there is condensate water collecting in the foil flex insulation of the bypass duct. I immediately got a bucket and put a hole in the jacket so I could drain it. I immediately shut off the static pressure control damper so it will close air flow to the bypass damper. Also unfortunately I noticed heavy condensate on the outside of the Daikin furnace assembly. Typically where I live the dew point gets anywhere from 76 to 80° this time of year at night and the temperature stays around 80°. Lastly it is in an unconditioned attic with spray foam traditional ceiling joists insulation. Two questions if I keep the bypass dampers closed will the static pressure cause problems in my system? I am not certain about building or fire codes but can I insulate the outside of the furnace to avoid the sweating of the unit?