Faster Hot Water Can Change Your Life

We’ve normalized the abnormal in our homes in so many ways that most people have no idea what kind of performance they should expect. If you’ve never lived in a house with a good building enclosure and HVAC systems, for example, you really haven’t experienced true comfort. The same is true for hot water. If you’re used to turning on the hot water and then doing something else while you wait for your shower to be warm enough, you’ve normalized the abnormal.

Options for improvement

As someone who has understood hot water inefficiency since I met Gary Klein over a decade ago, I’ve given up normalizing that particular abnormality in my home. Instead, I did something about it. With an existing home, your options are limited by the state of your plumbing system, the extent of the changes you’re willing to make, and how much money you want to spend. Let’s look at the options, starting with the most intrusive and expensive and finishing with the one I used.

1. Remodel the house to move the wet rooms and water heater closer together. In my house, the bathrooms are close to the water heater, but the kitchen and laundry room are farther away. I could reduce my hot water rectangle to a small fraction of its current value by switching the laundry room with the foyer and the kitchen with the den. That extensive remodel, however, would be way too expensive.

2. Install a demand-type recirculation system. Rather than messing with the plumbing system, another option is to install a pump that would circulate the hot water to the tap whenever you needed it. You could prime the pipes with hot water with a button, and occupancy sensor, or a fancier control system that learns your patterns and predicts when to deliver hot water.

3. Retrofit the current hot water pipes to reduce the volume of water they hold. The amount of water in the pipes between the water heater and the tap determines how long it takes to get hot water. Making the pipes shorter and smaller in diameter accomplishes that objective and reduces the time it takes to get hot water. This is the option I recently implemented at my house.

My hot water performance improvement

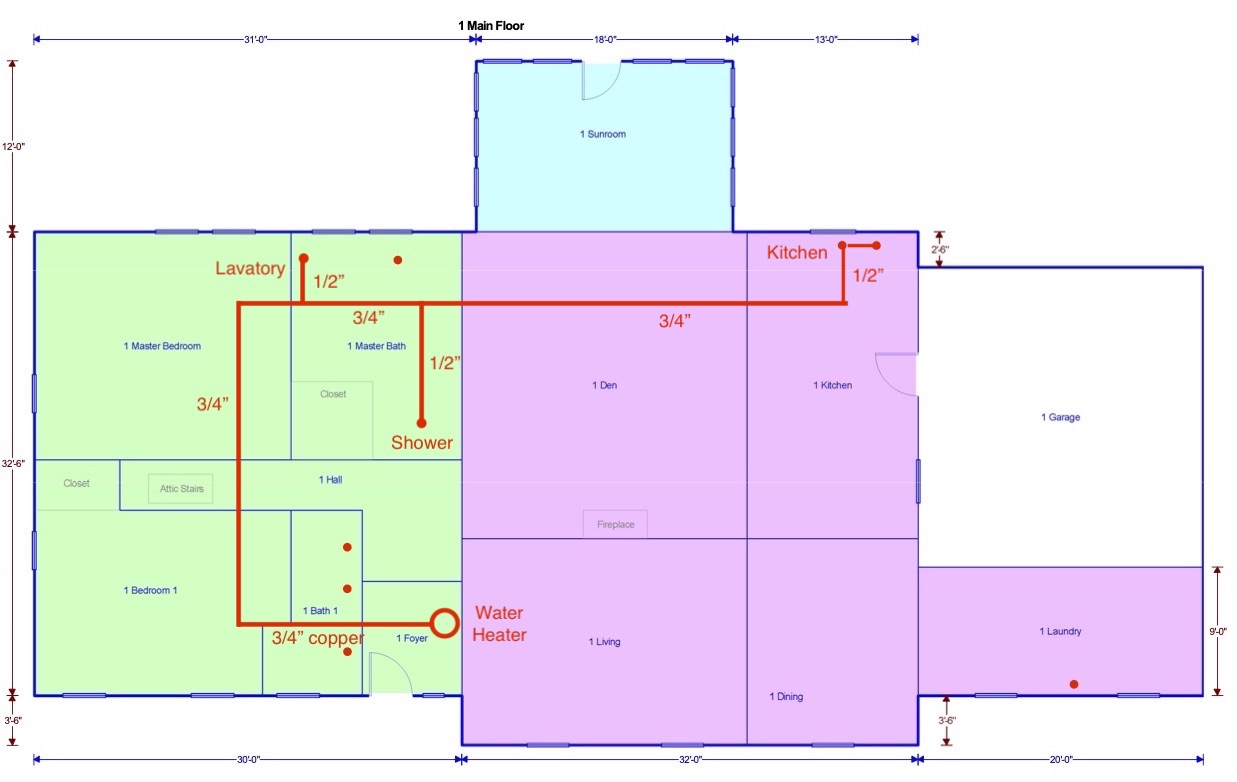

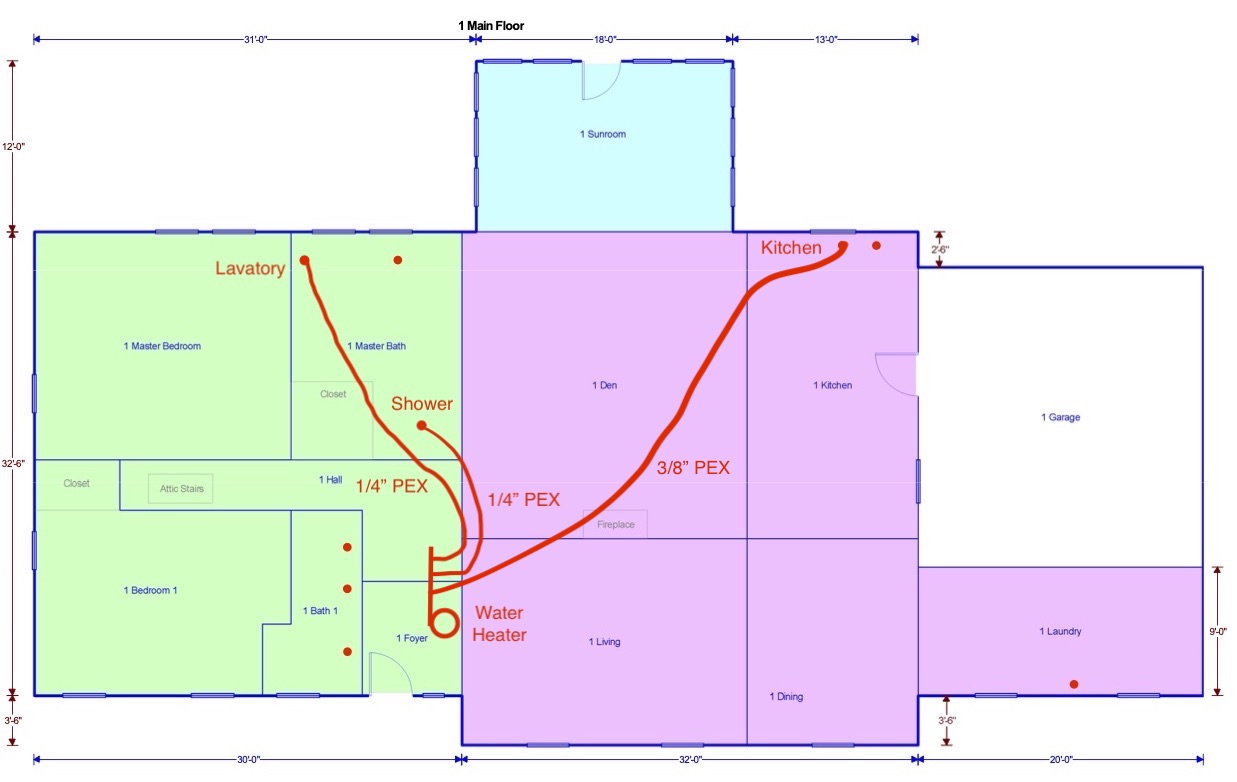

By running new PEX tubing to the three hot water fixtures that were the most inconvenient, I significantly cut the amount of water in my pipes and my wait times. I wrote about the lavatory and shower changes and results, but here are the updated before-and-after floor plans showing the kitchen as well.

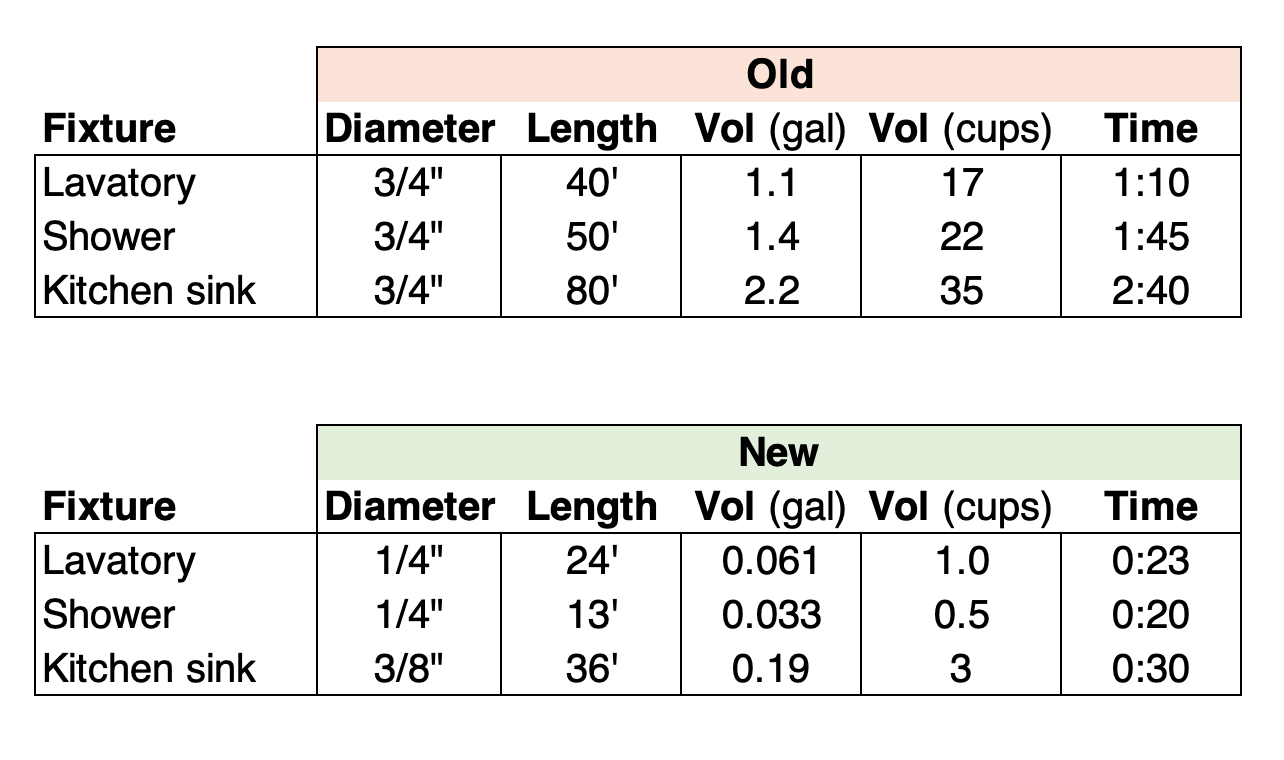

If you look carefully, you can see that the lengths of the shower and kitchen hot water pipes are way shorter after the retrofit. The lavatory run didn’t have as much reduction. Here’s a summary of the before and after numbers:

I cut both the length and diameter of these three runs, and that resulted in much better performance. The earlier article showed the lavatory and shower results, but the kitchen sink numbers are new. The volume calculations for all three are also new. I completed that kitchen run about a month after the other two, at the end of August.

One thing to note here is that the volumes shown above aren’t the whole volume between the water heater and the fixture for each run. They’re the approximate volumes affected by the retrofit. There’s still a few feet of 3/4″ copper pipe at the water heater and the manifold and also a few feet of 1/2″ copper pipe connecting the new PEX line to the fixture.

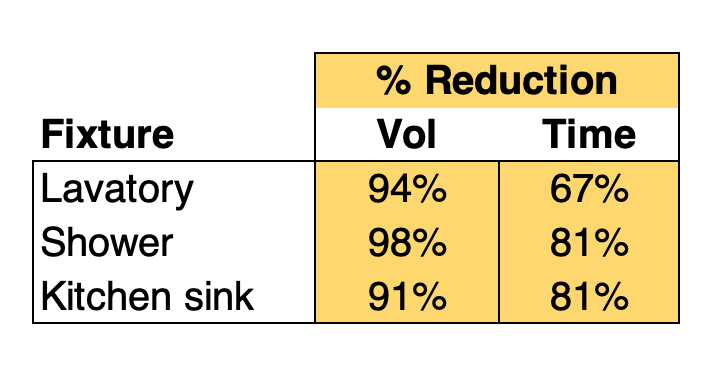

To give you a little more perspective, the table below shows the percent reduction in the volume of water in the pipes and the time I wait for the hot water to arrive.

As you might suspect, I’m quite pleased with how this has turned out.

How fast is fast?

Gary Klein, one of the gurus of hot water, wrote in his excellent Journal of Light Construction article about efficient hot water piping (pdf), “My goal is to achieve a time-to-tap of two to three seconds at a flow rate of about 2 gpm [gallons per minute].” That’s an admirable and achievable goal when you’re designing a new home. It’s not so easy to do, however, with option 3 above. Does it matter?

In my house, I got my wait times down to 23, 20, and 30 seconds. Yeah, three seconds for hot water would be awesome, but it doesn’t make a lot of difference to me. With the shower, for example, I used to turn it on, then go open the hot water faucets on the tub and the lavatory. Then I’d waste more than two gallons of water waiting. Then I’d turn off the other two faucets and take my shower.

Now I turn on the shower and get in after about 10 seconds. Yeah, I said above that it takes 20 seconds to get hot, but it gets warm at about 10 seconds. That doesn’t feel like a burden at all. Nor does it waste much water.

The other biggie is the kitchen sink. It used to take close to 3 minutes. Now it’s warm at about 15 seconds and hot at 30. When I wash dishes, I spend some time rinsing them first, so it’s no big deal to wait 30 seconds. If I just wanted to do a quick rinse or handwashing and the hot water wasn’t already there, it would be a little inconvenient. But I’m OK with that.

The other biggie is the kitchen sink. It used to take close to 3 minutes. Now it’s warm at about 15 seconds and hot at 30. When I wash dishes, I spend some time rinsing them first, so it’s no big deal to wait 30 seconds. If I just wanted to do a quick rinse or handwashing and the hot water wasn’t already there, it would be a little inconvenient. But I’m OK with that.

The joys of faster hot water

When you live with a problem like long wait times for hot water, you eventually normalize the abnormal. Architects, home builders, code officials, and plumbers could ensure that every house has fast hot water without having to spend a fortune to get it. The three options I mentioned above are the best ways to do it.

And if you’ve been living with the abnormal for a while, the joys of getting faster hot water will make you smile for a long time. My wife didn’t think she’d care or notice the change much, but she’s been raving about it ever since I finished the kitchen.

Eventually, though, you’ll stop noticing it because fast hot water will be your normal.

Caution: Prescriptive plumbing codes don’t allow pipes as small as 1/4″ so you may need an engineer to help if you want to go that small. You need to know the flow rate required at the end of the line, and you need to have sufficient pressure. To use 1/4″ PEX tubing, it should be about 1.8 gallons per minute or less. Also, if you need to run the PEX more than 25 feet, you’ll need to go to a larger size, too. To get a better handle on what you need, use this plastic pipe design calculator.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He also has a book on building science coming out in the fall of 2022. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

Efficient Hot Water Delivery With a Simple Tool

Why Your Hot Water Takes So Long

Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 26 Comments

Comments are closed.

I vote that Allison’s articles be adapted to elementary and middle school curricula everywhere, and then again, without modification, into high school curricula. Trying to convince adults is like pulling teeth.

Well, that’s an interesting idea, Paul. It reminds me of that quote from physicists Max Planck:

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

But I hope that my work has helped a few adults, too. :~)

Instant hot water is awesome! We have 5 second hot water for our shower and 2 seconds for our lav sink, I implemented an on-demand recirc pump with a button under our vanity near the shower. I used a dedicated return line as I was remodeling but it works almost as well with pushing it back down the cold water line. The button setups don’t waste any energy at all like occupancy sensors or timers and really – how hard is it to push a doorbell button? Saves so much water too.

Chris: That’s great! An on-demand recirculation system was my plan B if I hadn’t been satisfied with my pipe retrofit.

For people who don’t understand the two types of recirculating systems, there’s continuous (maybe with a timer) and on-demand. An on-demand recirculation system reduces the pump runtime by 98 percent and the heat loss by 90 percent, compared to a continuous recirculation system.

How did you find proper components for a push button recirculate system? Where? I’m mor familiar with commercial pumps, etc. and they cost way too much. Did you use low voltage from the push button to a relay?? I’m in the middle of a whole house renovation and dealing with this very issue in the design phase. Thanks

Sidney, there are packaged systems out there that have all the components and smarts. Here is one ecm choice from Taco https://www.supplyhouse.com/Taco-HLPE-1-Hot-LinkPlus-System-w-Hot-Link-Valve-1-2-NPT. I had a hard time finding others them but I know they are out there.

I teed off the hot water line from under my master bath vanity (right next to the shower) and brought that back to near the hot water heater which is where I installed the circ. Normally the line goes back to the water heater’s cold water input though my Vertex has side taps that I used instead. I ran low voltage doorbell wire and installed a doorbell button literally into the side of the vanity and another button in the guest bath (they wont get instant hot water but it reduces the time by 2/3). There are also setups where the pump installs in the vanity (outlet needed) and it pushes the hot water back down the cold line so you don’t need to install a separate return line. Ecm pumps are great there as they are so quiet. Or the pump can go on the water heater and there is a special valce under the sink. (Watts) The pumps turn off when they sense the hot water has arrived.

I strongly prefer the push button instead of the timer. The timer introduces extra power usage for the circ when it isn’t needed, and keeps circulating hot water when it isn’t needed, AND if you are outside the times you set it doesn’t do anything and you have to run the hot water anyway. Motion sensors are an in between compromise.

As Allison’s whole article is about, I can’t imagine not having this convenience and the amount of water is saves over time is staggering.

Sidney: There are several companies that make these systems. One of the best and oldest is the D’MAND Kontrols system. Here’s their page for residential systems:

https://gothotwater.com/shop_residential/

Allison, I remember I checked out the D’Mand system a few years ago, and I don’t remember exactly, but it was a couple hundred bucks, maybe $400? Their simplest system (pump, button, controller) is now over $1100! That’s getting close to the cost of the entire heatpump WH, and it’s disappointing. Too much greed?

The following is sucked out of thin air, but let’s say the pump system will save me 10% of water, and 15% of electrical energy, which in my case would be about $6/month for water, and $1.50/month for WH (heatpump). Let’s round it up to $8/month. Comfort?, absolutely! But it would be a loooong ROI.

On-demand re-circulation is the way to go, but we can’t have another Apple trying to make us believe that a pump with a button and $10 worth of circuitry is desirable and HAS to be had for $1100 a pop.

Highlighting the concept of normalizing the abnormal is a great public service – thanks Allison, we should all draw attention to this concept whenever the possibility presents itself. When it comes to modern construction practices, building to simply meet minimum code requirements has resulted in a normal that creates deficiencies in both human comfort and energy efficiency. How can we engage code committees to better understand the results of so many years of producing lowest common denominator standards? We need to do this.

Roy: That’s a great question. And it goes beyond codes, too. We need everyone involved in home design, building, maintenance, operation, and sales engaged. And it’s not just deficiencies in comfort and efficiency. The deficiencies also show up in indoor air quality, durability, and all the factors of indoor environmental quality, too.

We should sic my pal Robert Bean on ‘em for starters.

Code committees are under constant bombardment by lobbyists of builder groups. No code update gets through without a lot of back-and-forth with those groups, and that is number one direct reason for the slow progress in codes.

The indirect reason goes back to education of the public. Car buyers, for example, expect a certain level of performance from a Mercedes for their hard-earned money. For home buyers, on the other hand, the difference in performance expectation between a $200k starter 1200sqft ranch and a $1.3M 6000sqft “upgrade” home is usually small (examples based on Atlanta metro market). The focus is on the looks, the finishes, etc., and it has been for generations. Max Plankc definitely got it right.

Also, for anyone with a tankless heater, there’s a volume of cold(ish) water in the little tank that also has to be heated – so some more wastage there.

Great article and great project, Allison. But who am I to say? You already got the best review anyone could hope for: “My wife didn’t think she’d care or notice the change much, but she’s been raving about it ever since I finished the kitchen.” Priceless!

IMHO, Gary Klein oversimplified the efficiency analysis in his JLC article. I would disagree with a blank statement that a central home-run manifold system is bad. It depends on the layout, and it depends on the usage patterns, which would include number of occupants.

As with any BS simulation, the wrench in the gears is the occupant factor. For example, a single-story house with centrally located WH (2 bathrooms, 1 kitchen sink, 1 washing machine) benefits from a home-run manifold system (in conjunction with reduced diameter supply lines) when there is 1 occupant.

Chris,

I there any issue with “pushing it down the cold line.” I’m already nervous about the pressure on our PEX lines, but really don’t want to remodel right now. Our shower is 10 or 15 feet from the HW heater, and it takes a minute or two to get hot water.

Thanks, –John Weil

John: Yes, there could be an issue with using the cold water pipe as the return for a recirculation system. The water in a water heater is generally not suitable for drinking, and that gets more and more true as the water heater ages. Sediment builds up in the bottom of the tank from corrosion of the tank lining or sacrificial anode rod or both. Most people don’t flush their tanks to remove that sediment, but even if you do, it will build up between flushes. And because of the warm temperatures, you could have other stuff going on in there.

By pushing water from the hot water line into the cold water line, that potentially nonpotable water could be used for drinking. It shouldn’t be in the line very ling, but it’s possible someone will open the tap to get drinking water at the wrong time and get some of it. How big a problem is it? Not huge because they probably won’t get a glass full of water from the water heater. Even if they do get some, it’ll probably be diluted by some water from the cold line. I wouldn’t want to do it myself, but some people do. My recommendation is to run a dedicated return line if at all possible.

Thanks Allison,

Makes sense. Guess that also means no more warm drinking water from the tap, and no using hot water in the pasta pot to speed things up.

–John

Google suggested your wind washing post after I was researching spray foam insulation which was excellent, led me to this one and now I plan to go back through your entire blog. I own a 1940’s, gut remodel, 2 flat (because in Chicago it’s easier to strip an old house down to the studs than get permits for a new one!). The 1st floor/basement arr is duplexed for unit 1 with the second floor as unit 2 with bedrooms on either end and in the middle of a 20’x60′, east-facing, brick building. Compared to a lot of nightmare homes I’ve seen they did a lot right, but had some obvious misses (like no insulation except IN CHICAGO except in the small gap between the ceiling and the flat roof upstairs) that I would never have accepted if I done the renovation myself. Needless to say I have… “issues” keeping the east and west bedrooms anywhere near the same temperature as the middle. I recently implemented a partial fix to a hot water issue upstairs where the tankless water heater is in a closet on the far west end and the master bath on the far east. The hot water wasn’t triggering from low pressure and my quick fix was to flush the water heater. It seems simple, but I hadn’t every had a tankless before and didn’t realize how often I should flush it or how much it would help! I want to do a lot more so I’m pretty excited to read through your blog as I prepare for winter and the -30f temps predicted by the farmers almanac. If you’re open to questions from an undereducated engineer with a business degree I would love to pick your brain on a myriad of topics.

Thanks in advance for all the info I’m about to absorb!

Hi Allison, I have a thermosiphon loop on my water heater to take care of the one distant kitchen. The only power is a timer for an automatic shut-off to control back siphoning and that it not circulate all the time.

Charlie

Charles, let me quote Martin Holladay who called a thermosiphon loop an “energy nose bleed.”

No method (recirc loops, reduced diameters, etc) is free of energy losses, but I would put the thermosiphon in the “worst” category, and for some scenarios, even worse than not modifying anything at all. You mention a timed shut-off valve, trying to understand: what happens when the valve is off and someone calls for hot water?

I see I’m late to this blog post but I’ll comment anyway.

I’m on a septic and didn’t want to add more water to it than I have to, so I had a recirculation loop installed during construction. The Grundfos pump can be controlled by the dip switches in 15 minute increments (good luck with that.)

I bought a 4-pack of wifi smart outlets for $20. The pump is set to always on and plugged into one smart outlet. The other three outlets are in the kitchen and two bathrooms. Each outlet has a manual on/off button and at the click of any of those buttons, the automation triggers the pump to turn on for 4 minutes. The triggering outlet automation turns itself back on 2 seconds after the pump outlet is turned on. This confirms that the wifi actually worked.

The pump can also be triggered from our phones and Alexa/Siri/OKG, but clicking the little button is easier.

Mark, that sounds like an interesting solution. Just wondering, why 4 minutes?

It only takes two minutes for the hot water to reach all the faucets, but I gave it a small fudge factor.

I also insulted all the pipes (pex), so the water is still comfortably warm 30-45 minutes later.

At 60 psi, through 1/2″ pipe (a little less because it is PEX) you would waste 28 gallons in two minutes. My timer controlled thermosiphon recirc loop on the other hand is hot after pushing out only a cup of water.

Great article.

I found it by searching for the benefits of switching to PEX on a long run of copper to a distant bathroom. I was not thinking of a volume change, as the water pressure to the shower is just acceptable as is.

My thought was simply to reduce the heat dissipation through all that copper. Any idea of the relative contribution of less thermally conductive pipe vs reduced volume to the improvement in hot water delivery?