Hotels Have a Humidity Problem

If you travel with a hygrometer, as any seasoned traveler should, what I have to show you here is nothing new. But if instead you’ve never measured the relative humidity in a hotel room, I’ve got something interesting for you today. And I also have an answer to the question you may not have known you had. Yes, hotels here in the eastern half of North America have a humidity problem. But how bad is it? And why does it happen?

This summer I did a little book tour in the Northeast. I drove from my home in Atlanta all the way to Halifax, Nova Scotia and back, staying thirteen nights in eight hotels. I also spent four nights in a couple of Airbnbs and four nights with friends, but this article focuses just on the hotels. I carry my Aranet4 carbon dioxide monitor* with me when I travel because it provides good information about ventilation. But it also measures temperature and relative humidity, my interest here.

Week 1: 4 sticky nights in 3 hotels

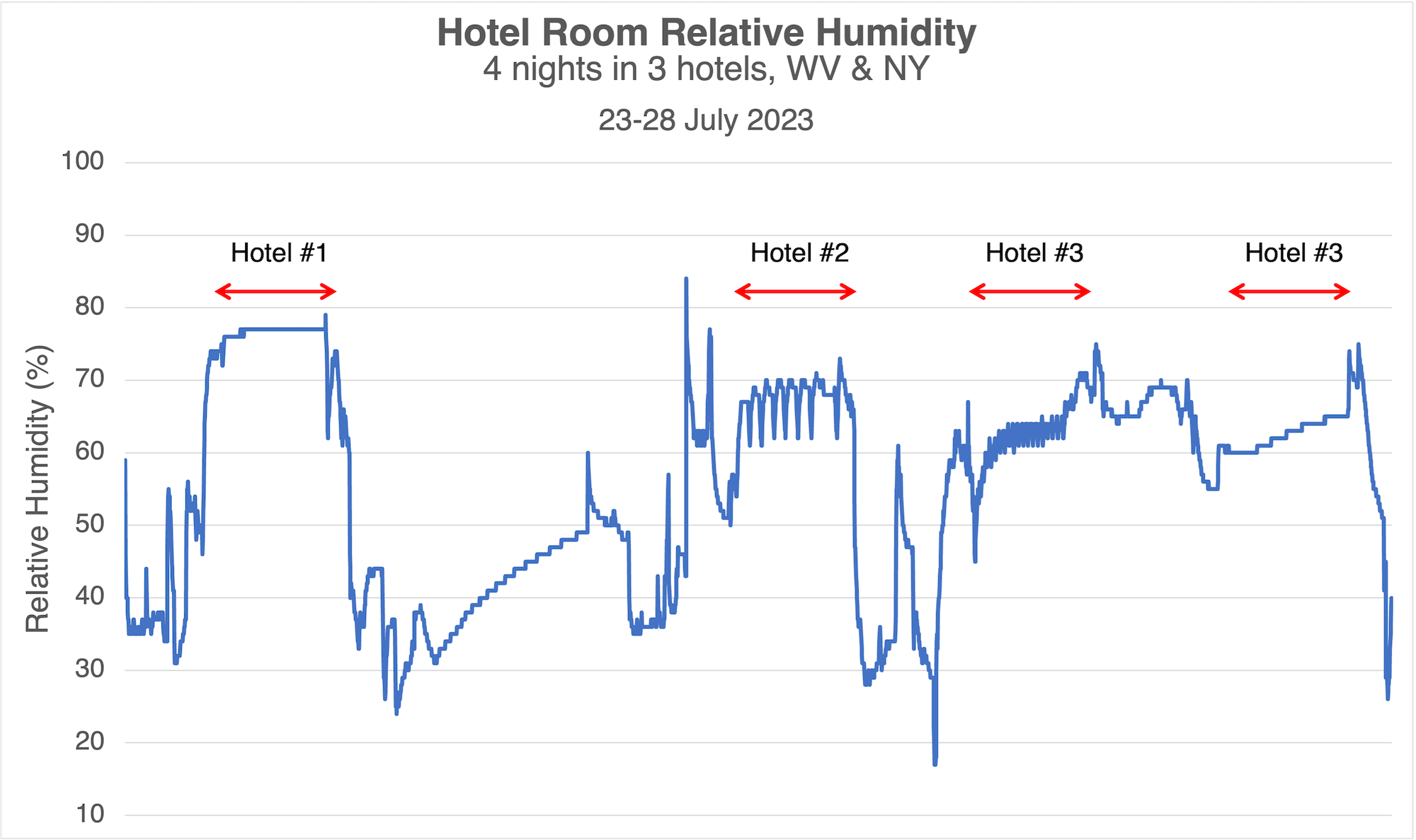

In my first week on the road, I stayed in hotels in West Virginia and New York. The first one was a cheap hotel. The other two were midscale to upper midscale. Here’s what the relative humidity looked like.

The cheap hotel (#1) was clearly the worst, hitting nearly 80 percent relative humidity. But spending more for lodging didn’t buy me much improvement. The second one still hit 70 percent, and the third one was above 60 percent both nights.

“But wait,” you say. “Aren’t you the guy who hates talking about relative humidity? Didn’t you say dew point temperature is better?”

Why, yes. I have said that. To explain, let’s start with the indoor design conditions from the Air Conditioning Contractors of America. At an indoor temperature of 75 °F and relative humidity of 50 percent, the dew point temperature is 55 °F. In the first three nights shown above, the room temperature was about 68 °F while I slept, and the dew point was in the 50s Fahrenheit. But I also had plenty of hours with the dew point in the 60s F.

On the last of those four nights, I kept the room at about 75 °F. That pushed the dew point up to as high as 67 °F. Not good.

Week 2: 5 nights in 1 stubborn hotel

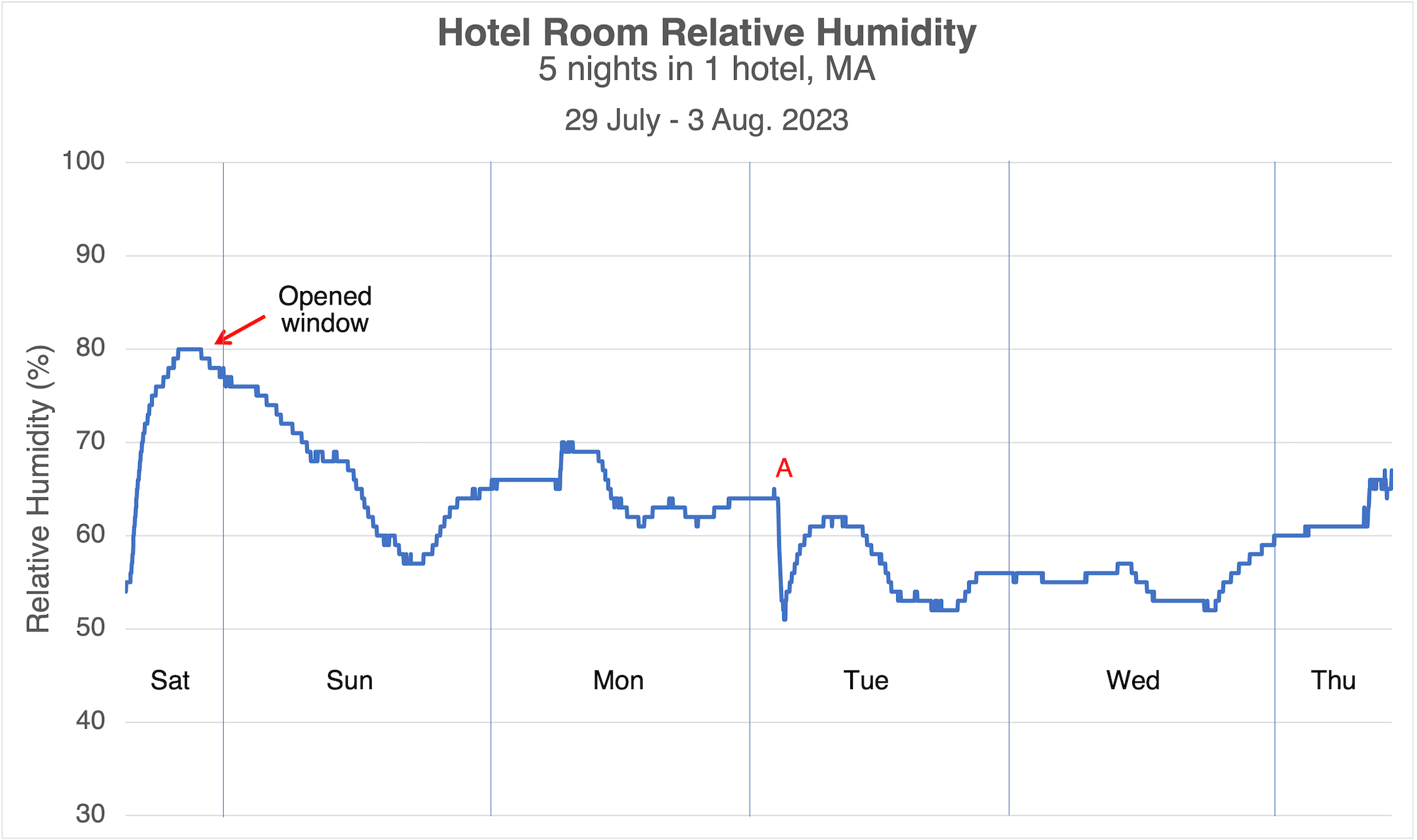

The next graph shows the data from a single hotel where I spent five nights while at a conference in Massachusetts. You can see that the relative humidity climbed to 80 percent on the first day. The weather was warm and humid that day, and it rained in the evening.

But then the weather turned beautiful. The nighttime lows were in the mid-50s F with daytime highs in the mid-70s. The outdoor humidity was low the rest of my time there, with dew points in the low- to mid-50s.

And lucky for me, I was on the second floor in a hotel that had operable windows. That Saturday night, after the cool, dry weather moved in, I opened my window. You can see that the relative humidity in my room fell through Sunday afternoon, even getting down to less than 60 percent. But then it rose and stayed in 60 to 70 percent range for the next day and a half.

Why? The outdoor air was dry. My window was open. I even opened the window at the end of the hall. Someone kept closing it, but I’d open it again when I walked down there. It’s an old building, and perhaps the rain had wet some of the materials, keeping things humid inside.

So what happened at point A? Well, when the afterparty in the hotel lobby ended at about 2 in the morning, I went back to my room. I opened the hall window again, and a strong breeze came in. That helped drop the humidity rapidly, but then either someone closed the window or turned off whatever fans were creating the negative pressure.

Finally, after nearly three days, my room dried out enough to stay below 60 percent relative humidity on Tuesday.

Last night: A little surprise

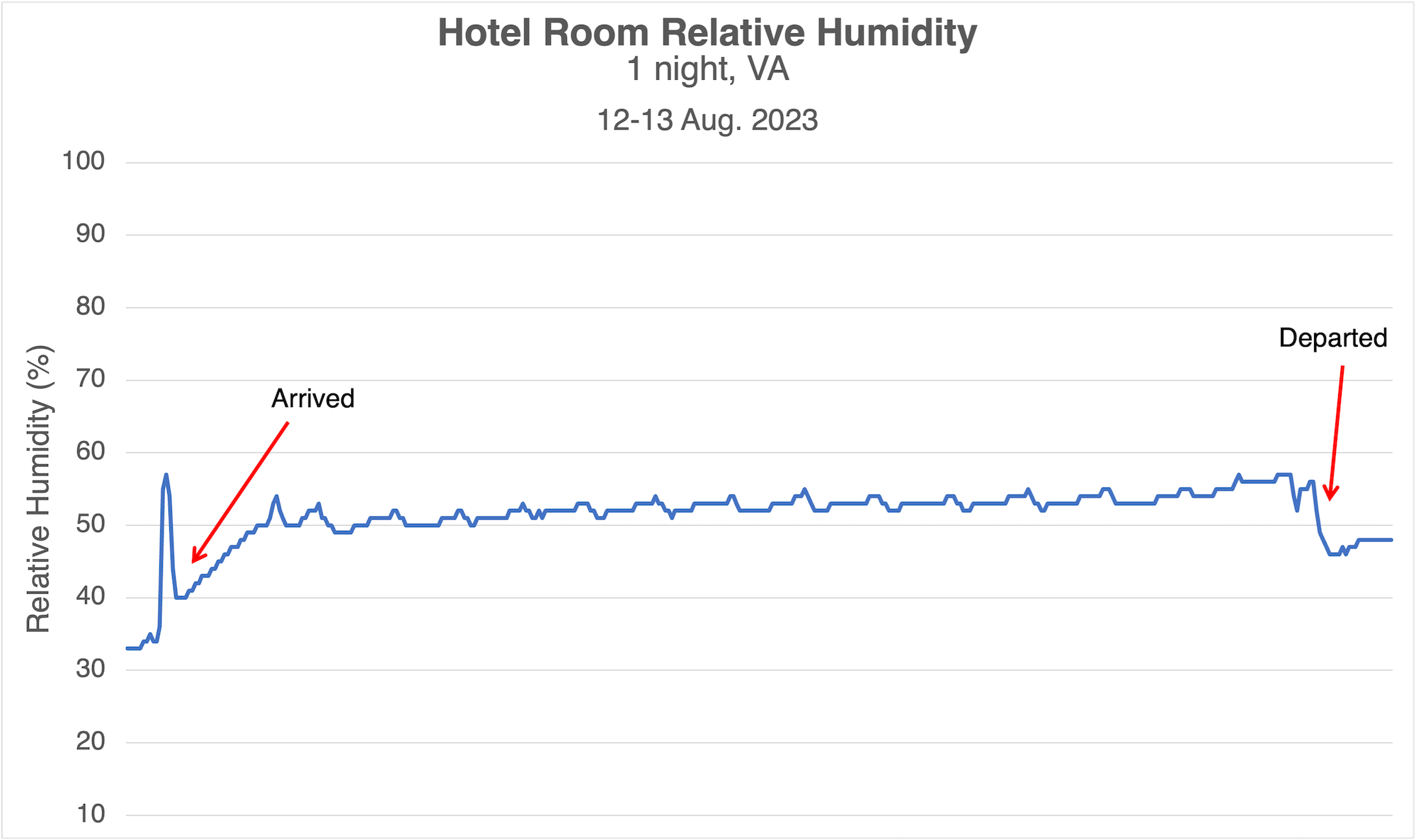

I’d gotten so used to seeing high relative humidity in hotel rooms on this trip that I expected the same on my last night. Instead, the relative humidity stayed in the low to mid 50s the whole night. The graph below shows those data.

My first thought was that maybe the filters were dirty. That could help reduce the humidity level because it would reduce the air flow across the air conditioner coil. Lower air flow means lower coil temperature and better dehumidification. So I checked them. As you can see in the photo below, they were clean.

Now, remember I mentioned a question you may not have known you had? The graph below, plus what I said earlier about my first three nights, shows what I was alluding to.

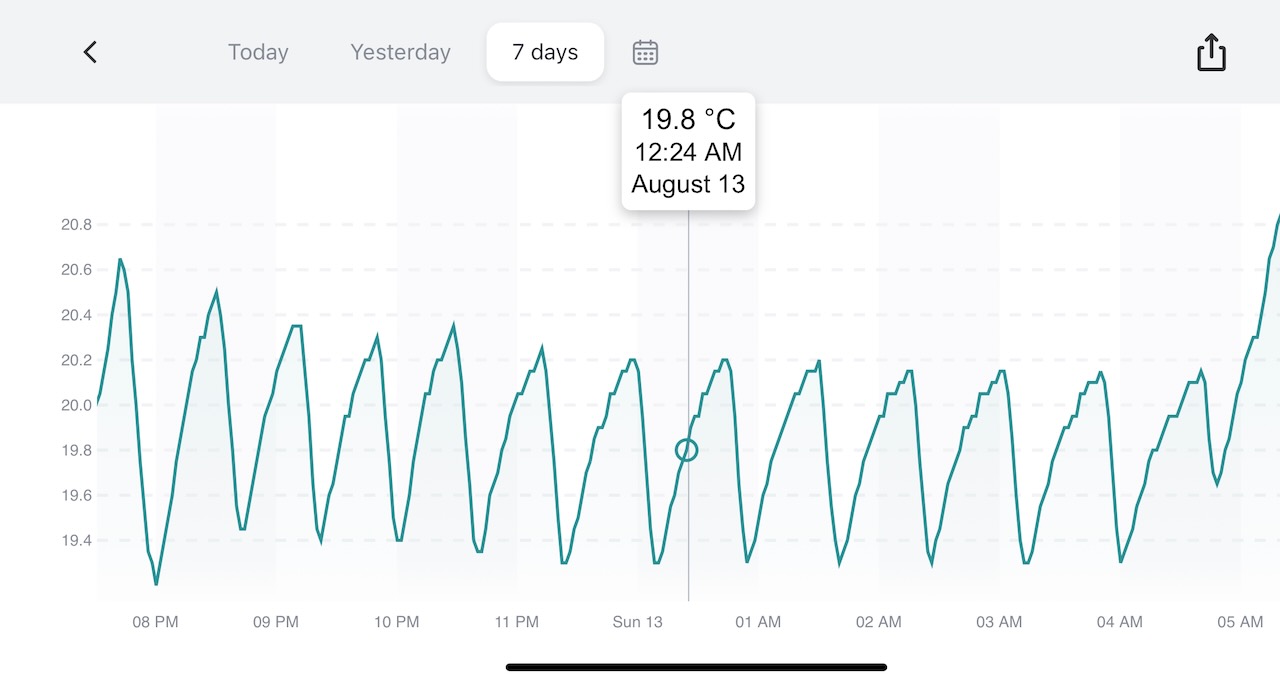

As you can see, the temperature in my that night ranged from 19.3 °C (67 °F) to 20.6 °C (69 °F). That’s about what my rooms were on the first three nights of my trip. It’s pretty darn chilly. By making the room so cold, though, the air conditioner keeps wringing more moisture from the air. The dew point temperature was 51 °F (10.5 °C).

And that question of yours was, “Why do hotels keep the rooms so cold?” Right? Now you know.

What’s the problem with cold rooms and high humidity?

First, there’s the comfort problem. Keeping the temperature at 68 °F (20 °C) isn’t comfortable for a lot of people. And if the humidity is still high, you feel cold and clammy. But then you raise the thermostat setpoint, and the room starts to feel warm and sticky. It’s hard to find a middle ground that’s comfortable.

![Mold growth on the backside of drywall on an interior wall in a hotel [Photo courtesy of Chris White]](https://www.energyvanguard.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/mold-growth-microbial-infestation-hotel-interior-wall-high-humidity.jpg)

Also, by keeping the room so cold, the chance of humid outdoor air leaking into the building and finding cold surfaces increases. That’s what happened in the photo above. Chris White, an engineer in Louisiana who does a lot of mold and asbestos work, took this photo of an interior wall in a hotel. The back side of the drywall is covered with mold for this very reason.

So yeah, the humidity problem that hotels have has real consequences.

How can hotels fix their humidity problem?

To fix the high humidity problem, hotels need to get serious about the building enclosure, ventilation, air conditioning, and dehumidification. It starts with the building enclosure because the first step is to reduce the amount of humid air infiltrating into the rooms.

That begins with airtightness but also includes ventilation. Why ventilation? Because most hotels have exhaust-only ventilation in the bathroom. When the fan pulls air from the room, other air has to come in from somewhere to replace it. I know of at least one hotel (the Hyatt Regency in Seattle) that has dedicated makeup air. (Read about it here.) Most, however, rely on infiltration.

They also can choose an air conditioner that has good moisture removal capacity. The one in my room on the last night clearly was able to remove a lot of moisture. And it needs to have the air flow set correctly to slow down the air, making the coil colder and removing more moisture.

Finally, they need to consider supplemental dehumidification. There will be conditions when the above measures just aren’t enough.

Sum and substance

Hotels have a humidity problem. I would love to check into a hotel in summer in the eastern part of North America and not have to choose between cold-and-clammy or cool-and-sticky. I’d like not to worry about the indoor air quality problems resulting from that humidity. What’s it going to take to get them to fix it?

But there is one thing I can be happy about. At least I didn’t see anything as bad as the air conditioner in that hotel in Mississippi a decade ago.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can subscribe to the Energy Vanguard newsletter and follow him on LinkedIn.

Related Articles

Adventures in Hotel Bathroom Ventilation

Have You Seen What’s in Your Hotel Room Air Conditioner?

10 Consequences of Keeping Your Home Really Cold in Summer

* This is an Amazon Associate link. You pay the same price you would pay normally, but Energy Vanguard may make a small commission if you buy after using the link.

Comments are welcome and moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 9 Comments

Comments are closed.

Hotels won’t fix these problems unless / until there’s immediate profit from doing so. While such conditions cause health problems, I doubt there’s much chance of costly legal action against hotels since guests dwell for very short stays. An exception may be in hotels that cater to extended stays, but the transient and economically disadvantaged nature of those guests may impede organizing claims.

Some relief may be around the corner in the form of inverter-driven PTAC / PTHP compressors. In the course of hundreds of nights in hotels, it has been my experience that room ACs are so oversized that they run for just a few minutes at a time, and the so-called “low” fan speeds really aren’t very low.

I have an 8 kBtuh inverter window AC cooling and dehumidifying a detached shed, and it is amazingly quiet, efficient and excellent at dehumidification…I’ve measured discharge air as low as 38*F (almost a 40 degree split) and RH of 45% in that leaky uninsulated shed. I paid about $400 for it, a Midea “U-shaped” model about a $200 premium over a code-minimum unit.

When that tech makes its way into PTAC / PTHP, the situation has potential for substantial improvement if the controls are set up to optimize dehu under part load conditions. We shall see.

Another option would be to have the code updated that would require more appropriate units with better turndown etc.

Your experiences match mine in hotel rooms with PTACs. You mention the increased likelihood of microbial infestations but higher RH can also result in dust mites in bedding. Since dust mite droppings are a common human allergen this is a concern as well.

Fortunately, I am seeing improved AC conditions in newer or recently remodeled rooms. Fan speeds are lower and the fans aren’t set to run 100% .

Hotel 1, 2, and 3, . . . what about Motel 6?

Some of the issues in hotel rooms are the same that are in many commercial buildings. They are NOT treated like residential houses when it comes to how they are used or operate so if you are a house only guy looking at it you will miss allot of special use case issues.

Hotel rooms are NOT conditioned non stop like a house. They are left with the AC off in many cases until the customer walks in the door and turns on the AC.

How long has the AC been off. A day a few days a week or more. You will never know. And in that time everything in that room has been sucking up moisture and gaining heat.

Now you walk in and turn the AC on and you want it cool now. So it takes an oversized unit to get that initial heat out quickly. Then it will take days for it to remove all the moisture from the items in the room.

And this is assuming that the bathroom actually has an exhaust fan that works which 95% don’t so it you stay at hotels often you know to crank the AC way down when you take a shower so it runs even longer.

Now you have hotels with those stupid occupancy sensors that shut the AC off when no one is there and the unit has to be even bigger than the normal room and they will always be humid.

Couple all of those issues and more with things like the seal under the door to the hallway doesn’t seal… It has a 1″ gap to let smoke and hot air in from the hallway. And then the fact that PTAC units are just junk. The exact same sized window unit would work just fine and keep it dry and use less power. It’s just that PTAC units are cheap in massive quantities. They are basically a really low quality window unit and many aim for high airflow and throw instead of cold air.

I spend allot of time in hotels and the better half spends half the month in them all across the US canada, mexico and a few other south american countries. They mostly all suck when it comes to AC performance. Anything on the coast anywhere will be moldy so always stay in a brand new hotel any time you visit any coast.

This problem with hotel room cooling sounds very similar to the problems you hear about with mini split systems in houses where there wasn’t good sizing done for the mini split systems. Both have high humidity issues in humid climates like the US East Coast during the cooling season.

I wonder if the principle that “A/C dehumidifies” is sometimes overstated and misapplied. I’ve certainly noticed that running the A/C at home will reliably lower the dew point temperature (at least temporarily), but the RH may remain almost constant, due to the lower temperatures. Even a properly sized system can be a problem: as you’ve shown, cooler surfaces exposed to damp air can become a mould garden. Infiltration and ventilation are definitely vital pieces of the puzzle!

Another example: my aunt once travelled on an inter-city bus where the driver kept the cabin unbearably cold, apparently in an effort to prevent condensation on the windows. Adequate ventilation (perhaps even with some heating as required) might have been just as effective, and more comfortable.

For my DIY home HVAC control, I’m quite liking the results of using the humidex as the basis of the set points, but even then, what’s comfortable indoors during the winter isn’t necessarily comfortable in summer. I’m also liking the idea of using indoor and outdoor dew points to decide how much ventilation to use. (My home is also far from airtight, and it’s amazing how quickly the indoor dew point will track the outdoor.)

Well I hate to admit, but I spent years working with hotels around the country and in the Caribbean on the humidity problem. Sometimes we would make some improvements but within a few years it would be back to normal which is mildew and moisture problems everywhere.

Many hotels do have large fresh air systems on the roof the air goes through a evaporator coil and then blows into the hallways and more recently with new codes fresh air is ducted directly into the guest rooms. The rule is about 60CFM fresh air per room. The bath exhaust vents if properly commissioned suck 60CFM out.

The newer PTAC designs have added an extra tiny compressor that adds 50Cfm of fresh conditioned air to guest rooms where they don’t have dedicated fresh air systems. Not all hotels even know what I’m talking about and they don’t maintain these systems. Amana has a new recall on these “fresh air” PTAC units cause a few have been catching on fire.

The problems are too many to list. I am a contractor and years ago I started out contracting to hotels to haul the PTAC outside and soak them down with coil cleaners and really clean them but a national company started cleaning the ptacs in the guest room using a machine sort of like a carpet cleaner, but no way that is the same as soaping and cleaning outside with a garden hose. We would flush out tons of slime from each PTAC. I don’t do it anymore (thank God) but I see the filthy PTAC’s more often these days. The hotels don’t even check the work of the cleaning companies.

You are right about the temp. problem I don’t believe in just turning down the t-stat so low I find 72° to 74° is a good compromise. Most guests set the temp. to 65° and leave it there. The PTAC’s don’t drain very well and usually become a pan of water with a fan blowing over it fed by a cold wet coil. Some don’t even have drains and the water is splashed by the condensing fan against the condenser coil to evaporate the water and cool the condenser coil. By early summer the old indoor blower wheels would start water wheeling behind the evaporator coil because the drain channel between the indoor and outdoor half of the PTAC would be clogged with slime. Next the carpet under the PTAC will get wet and eventually the plywood floor under the light weight concrete floors start to rot, they clean or change the carpet because of the smell. Then they have contractor “quick” patch the floor.

Quite a few properties don’t even know they have a ventilation system so they don’t maintain them.

In the decade before the Covid year I was contracted to study these problems and try to solve them esp. in the south and along the coast but hotels now are much more spend thrift they just have the housekeeper clean the mildew and put a dryer scent sheet inside the PTACs.

I should mention a lot of hotels use motion sensing t-stat that float the temp. when you leave the room but usually they setback only to 74° at the most and some t-stat even sense humidity and slow the fan down and slightly lower the room temp. to fight humidity.

The windows and patio doors are the big unknown factor. Most the time opening the window will add heat and humidity but people still do it so they can smoke weed or cigs. or just get more fresh air then the PTAC fills up with water and doesn’t drain and so it goes.

I feel like the biggest problem is just too much A/C – I know that should be dehumidifying the rooms but it isn’t and that dew point problem is real when the windows is left open or outdoor summer air infiltrates through the walls from outside.

These air conditioners aren’t like residential split systems – they end up like slimy swamp coolers that never really get cleaned even though the silly air filters look clean.

Try cleaning a mini split wall cassette after 8 years the coils get clogged with mildew deep inside.

Water based coils with a central chiller have similar problems of course because they are usually old but maybe not as bad as PTACs because PTACs just don’t drain.

I remember in July in Dallas Texas maybe 10 years ago a GM was so upset that I set a limit on all the new guest room thermostats we installed so they would only go down to 67° . She called corporate and told them since it was 102° outside her guest needed the t-stat to go to 65°. So they caved and I had to show her staff how reset what I had done. If it’s over 100° outside it’s more comfortable to keep your room like >74° since if your cold as soon as you go outside you feel like your in a blast furnace. I bet her staff never bothered to change the settings on 130 rooms.

I do know good maint. guys that just turn off all the setbacks as soon as they learn how when the real problem is the A/C isn’t working right and 90% of hotel maint. guys can’t work on A/C’s at all, they just change them out or give you a different room.

I’ve noticed many of these PTAC systems will keep the blower running after a call for cooling has been satisfied; often with a timeout but sometimes continuously. Nothing like re-evaporating bunch of condensate back into the dwelling space…