Bad Advice About Indoor Humidity in Cold Weather

It’s that time of year again. The cold weather has begun here in the Northern Hemisphere, and people are talking about raising the humidity of the indoor air. I’m certainly no fan of bone-dry air, having experienced too much of it when I lived in an old house in Philadelphia. But I also know that keeping the humidity too high in winter can cause problems. Harvard University, in fact, once had to tear down a 17 year old building because of bad advice about indoor humidity.

The cause of bone-dry indoor air

Before I jump into that bad advice about indoor humidity, let’s first look at why the air in your house might be so dry to begin with. I’ve covered this before so I won’t go into all the details here. Here’s a quick rundown of the cause of dry indoor air:

- Cold air is dry air. The lower the temperature, the less water vapor will be floating around in the air.

- A leaky house allows a lot of cold, dry air to come in and mix with your indoor air.

- Two of the driving forces behind air leakage are wind and the stack effect, both of which can be higher in winter.

- When cold, dry air leaks into your house, it lowers the indoor relative humidity.

- The leakier your house is, the drier the indoor air will be in winter.

Clearly, all this means that the first step to keeping your indoor air from being too dry in winter should be air sealing. It’s a pretty simple concept, right?

A humidifier can help

Unfortunately, many people don’t understand the reason their indoor air is dry in winter. So they don’t jump to the logical conclusion of stopping the bleeding. Instead, they put a bandaid on the open wound: They start adding water vapor to the indoor air with a humidifier…or two or three.

Yeah, that can raise the indoor humidity. If you throw the right amount of humidification at it, you may even get to a reasonable indoor humidity. For a leaky, poorly insulated house in a cold climate, that reasonable humidity might be only 30%.

But it’s gonna cost you. Running a humidifier isn’t free. It takes heat to get that water into the air. And as you keep humidifying the air in a leaky house, that now more expensive air keeps leaking out. Then you have to humidify the new dry air that leaked in.

Clearly, reducing the air leakage should be your first priority in keeping your indoor air from getting too dry. Then humidify, but not too much.

Humidity advice from health experts

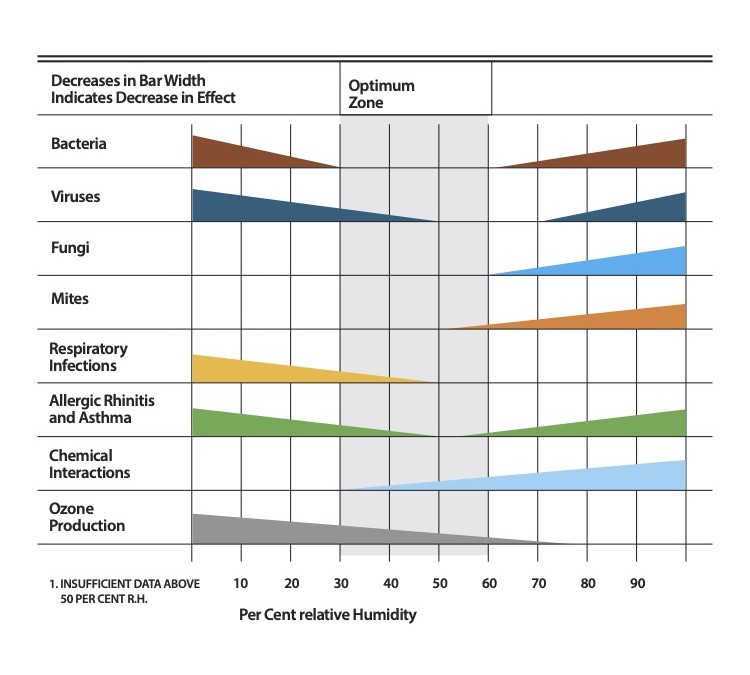

We’ve all been living through the COVID-19 pandemic for a while now. For the first time in a long time, we’re paying attention to what health experts are saying. One bit of advice we’re hearing from them is based on research on how the indoor relative humidity affects viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens. This line of thinking goes back at least to the 1980s with a paper that introduced what has become known as the Sterling chart (below).

That’s good information to have. It’s not enough, though, because…

A humidifier can rot your house

Here’s the thing about water vapor and cold materials, though. They love each other! If you live in an older house in a cold climate and someone tells you to keep your indoor air at 50% relative humidity, that’s likely to cause problems.

Yes, some of that humidity will leave the house entirely and get lost to the outdoors. Some of it, however, will pass through walls with cold sheathing and studs. And there it’s likely to find cold materials and stick to them. The more water vapor you put in the indoor air, the more you may be adding to the inside of your walls.

And the more water vapor you put into those cold walls, the more likely you are to cause those walls to rot or grow mold. If you’re humidifying the air for health reasons, then, you may actually be making your indoor air quality worse, not better.

Remember that Harvard building I mentioned? It was called Werner Otto Hall and was demolished in 2008. Why? The people in charge decided, because the building housed delicate art pieces, to keep the indoor conditions at 70° F and 50 percent relative humidity. They also decided to keep the building under positive pressure. That meant that humid indoor air leaked outward through the walls. Long story short: They rotted the building so badly it had to be torn down after only 17 years.

Bad advice about indoor humidity

Controlling the indoor conditions for health is absolutely a good idea. But you’ve got to understand the big picture. A house is a system. When you make a change to one part of the system, it has impacts on other parts. That’s the case with trying to crank up your indoor humidity to keep the viruses at bay. You may be creating other problems inadvertently, which is another reminder that a house is a system. Eric Sevareid said it best:

“The chief cause of problems is solutions.”

In short, it should be OK to use a humidifier to raise the indoor humidity in a leaky house in a cold climate to 30 or 35 percent. Once you start getting up to 40 percent, though, your solution may be the cause of new, potentially bigger problems. If someone tells you the relative humidity has to be 50 percent, that’s bad advice. Keep in mind that it’s usually stated as a range because not every house can take 40 or 50 percent.

Remember that the cause of dry air in winter is air leakage, so air sealing is the first and best way to keep your humidity from going too low. And it has the additional benefit of making your house less susceptible to moisture damage.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

What Is the Best Indoor Relative Humidity in Winter?

Controlling the Humidity in Your Home in Winter

Humidity, Health, and the Sterling Chart

Photo of humidifier by Bill Smith from flickr.com, used under a Creative Commons license.

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 44 Comments

Comments are closed.

Oh yea, I remember when I was a kid growing up in Illinois. Every time you touched a doorknob in the winter you got a shock. Carpet and static electricity with dry air. We were tough back then. We didn’t need a humidifier. Those were the days 😉

I do remember occasional nosebleeds being a problem during the winter too.

In the arid Southwest, we experience low humidity even in cooling season. Indoor humidity in my previous home ranged from 25% to 35% throughout most of the year round (it might reach 50% during July-August monsoon season.) You just get used to it, virus transmission not withstanding.

When there’s no an actionable heat load, the only practical way to mechanically add moisture is with steam. However, with outside dew points often in the single digits, steam humidification would be cost prohibitive, not to mention a huge water waste!

I built my new home extremely tight (< 0.6 ACH50), primarily to keep out dust and bugs, but it also retains internally generated moisture extremely well. Simply foregoing the use of kitchen & bath fans to exhaust moisture from showers and boiling water keeps indoor RH between 40% and 50% year round.

Tight construction can backfire in cold climates if one isn't careful. A layer of exterior insulation is the best defense against condensation inside wall cavities. The exterior-to-total-R-value ratio required to keep walls dry depends on the minimum outside temp and maximum coincident indoor RH.

This is another aspect of managing the dewpoint or getting managed by it. I’ve said and written before that it is possible to “total” a structure via misuse of a thermostat. I regret Hahvud’s loss but am glad to learn of another example for my arsenal of humidity uh-ohs.

I grew up north of Boston and attended school in Cow Hampshire. I disliked winter’s indoor dry air so much that it contributed to my move to swampy Florida…the skin on my knuckles would crack and bleed up north!

I’ve long thought 45% RH (summer) to be nearly ideal, and that seems to be validated by the Sterling chart above.

Curt, besides dry hands and chapped lips, my biggest problem with dry air when I lived in Philly those two winters was that the skin on my calves got super dry and really itchy. Now I can tell when the RH goes below about 25% because that same thing still happens.

Allison, one of those issues that I have not seen addressed relative to indoor humidity levels is wood shrinkage, primarily wood floors. People who install these floors are telling people that they need humidification to keep the floor from shrinking too much. I have seen wood floorboards shrink and open up gaps between the boards. They tend to close up in the summer when humidity levels increase again. In the meantime, though, the crud that people normally bring into homes from outside collects in the gaps when they open up.

I think that you know where I am going with this observation. Is there an optimal humidity level for wood floors?

Matt, yes, wood shrinks when it dries and swells when it wets. Joe Lstiburek covered this in an article called Wood Is Good…But Strange. I used reclaimed hardwood flooring in the house that I built 20 years ago and overventilated with an HRV in winter. The indoor humidity dropped below 15%, the lowest my hygrometer would read. The tongue-and-groove ceiling popped, and gaps opened up between the floor boards. I dialed back the ventilation and started using a standalone humidifier to get up to about 30% in cold weather, and everything was fine. Will 30% work in Saskatchewan? Maybe. But if it’s an old house that would be at risk with 40% RH, I’ll take a little bit of gaps in the floor over rotting walls.

Very helpful articles I shared! Many here in Southern Appalachia heat with wood, and believe that the fire somehow consumes water vapor to dry out the house. My efforts to explain this at best result in glazed eyes. I appreciate the simple explanations.

I live in the opposite situation, 460 square foot, air tight ICF (vapor barrier) house. I have had a crash home course in humidity management. Windows closed? Dehumidifier on! But I’ve also seen how quickly humidity goes down when opening the south facing windows on a sunny winter day.

Very interesting!

Richard, your observation about opening the windows in winter can help you save some energy. You can dry out your indoor air in winter simply by ventilating more. You don’t need a dehumidifier when you have access to all that dry outdoor air, and fans are cheaper to run than compressors.

@Richard wrote: “I live in the opposite situation, 460 square foot, air tight ICF (vapor barrier) house. I have had a crash home course in humidity management. Windows closed? Dehumidifier on!”

As I’ve often said and written… in new construction, I consider dehumidifiers to be an expensive band-aid. It’s better to attack the problem (excess moisture) through proper design than treat the symptom, forever. After all, a big reason for building a tight, super-efficient home is to reduce HVAC operating costs. Running a dehumidifer does just the opposite.

Common causes for excess indoor moisture include excess ground moisture due improper roof or site drainage, ineffective spot exhaust in kitchen/bath/laundry, leaky envelope, and/or poor HVAC design or installation (leaky ducts , high sensible ratio in cooling mode, poor air distribution, etc.).

Your situation made me pause to consider if there may be an exception: What if none of these things apply? Is it possible for a house to be small enough and tight enough that moisture from breathing and perspiration could raise RH to unacceptable levels? Wow. In that case, I guess addressing the source means getting rid of one or more occupants!

Seriously, I agree with Allison that (minimal) continuous ventilation would be preferable to running a dehumidifier in winter. Given your location, and that your walls are ICF, exhaust-only ventilation would work fine in lieu of wintertime mechanical dehumidification. Start by extending the run-times of spot ventilation.

Lastly, It’s possible that your enclosure is so tight that spot exhaust may be ineffective. Pressure diagnostics would reveal this. Maybe all you need is a pressure regulated make-up vent…?

I used to describe dehumidifiers the exact same way – “an expensive Band-Aid”, but the ever-more humid climate here in NoFla has me waving a white surrender flag at least with retros…although in fairness, at least to date I haven’t felt the need to add one to any of our custom new construction homes…yet.

HRV recover heat only. ERVs, the membrane type recover upwards of 82% of the moisture and heat both summer and winter. The right ERV is used in the bath to bring in outside air and exhaust the humidity. Depending on the particular situation, use of an HRV may be better. The best ERVs do not allow odors to pass across the membrane thus providing fresh air to the space and removing odors. This is also a very efficient way to manage CO2. Super tight structures with occupants will soon have an abundance of indoor CO2. You will probably notice this before you notice the moisture. Outside air has a CO2 concentration just above 400 ppm, Exhaled air is at about 40,000 ppm. Demand Control Ventilation DCV has three parts to manage with one system. CO2, Relative Humidity and tVOC or for most of the world that means odors but it can be lots of things.

It has been my experience that most doors and windows themselves are better than the installation issues. Check the gap around them and most have enough unoccupied space to allow massive extraction of air from the space with no appreciable drop in pressure. A foam sealant for doors and windows can greatly reduce the air leakage enabling much better humidity management without compromising buildings or occupants.

Good info.

Some helpful links

Grandma’s House. Starts out cold and dry. Then stuff happens!

https://youtu.be/jgnzdrC8AJ8

Data logging Temp RH Displays

Govee Bluetooth Thermometer Hygrometer, Indoor Digital Humidity Temperature Monitor with APP Alert, 2 Year Data Record and Export, for Nursery Room Greenhouse and Incubator Humidor

https://smile.amazon.com/stores/page/F77E1B3F-8A38-490C-9B96-E34311596F44?ingress=2&visitId=ec8daabc-d166-4f4d-9503-6145ee46bbb2&ref_=ast_bln

Heard about these from Steve Rogers at TEC

Allison,

Is part of the cause of dry indoor air during the winter the gas forced air condensing furnaces that many of us have in our homes?

Rob,

Although furnaces are often blamed for dry air, they are not the cause. Duct leakage on the return side can bring in dry outdoor air. Unbalanced duct leakage with more leakage in the supply ducts than in the return ducts can lead to negative pressure in the house, which drives more infiltration. But furnaces don’t destroy water vapor. When houses get too dry in winter the cause is always related to too much outdoor air getting into the house.

Confused about the source of the water the furnace produces. If they don’t destroy water vapor and outside air is dry, where is all the water coming from? Referring to modern 95+% efficiency furnaces used in northern climates. These have two side wall tubes — one input, one output, plus require a floor drain or reservoir with pump to remove the water. Always amazed by the amount of water I see coming out of the drain tube from the furnace. My current system has no duct humidifier or water line leading to the furnace.

There are times here is SoCal when the humidity gets down in the single digits outside, summer or winter. I’ve used a couple of ultrasonic humidifiers to keep it out of the 30% range at times. I have some acoustic guitars that don’t like it that dry and neither do I. Much to my surprise, I also found a connection to my gas stove burners burning yellow and my ultrasonic humidifier. After having GE come out and warrantee the burners, regulator, and not fixing the yellow flame issue. I found that even 30 ppm RO water in an ultrasonic humidifier will cause my burners to run yellow from the calcium compounds floating around in the air. I don’t imagine this helps with dust or is good for your lungs either. I now run the RO water thru one of these “zero” water filters and the result is zero ppm, no fine particles in the air and bright blue burners. And the zero water filter lasts a very long time when you are putting 30ppm water in instead of our 440 ppm water from the tap.

I battle with my wife over this everytime one of our kids gets sick. She brings in the humidifier and blasts it in their room with the door closed. I try telling her having it on a low setting will work better and wont cause mold to grow… Great post lots of really good info!

One water issue that has not been mentioned yet is wet crawlspaces or basements. They are a particular problem in the Ohio Valley area. I have been in my share of them. Some of the water in the basement or crawlspace often travels up into the building and condenses on cold surfaces in the occupied part of the building.

The monitoring being done in the ROCIS monitoring project showed an absolute cause effect relationship between indoor particulates and use of ultrasonic dehumidifiers. My recommendation — don’t use them!

I agree unless the input water is truly pure 100% no dissolved minerals…and I suspect the cost of such pure water exceeds the energy cost of simply boiling regular water.

I grew up in New England in the 1960s and 1970s and our winter humidification consisted of an open pot of water on the woodstove as well as the water required by Mom’s many plants that summered outdoors but wintered indoors. House plants make excellent humidifiers and have other health and quality of life aspects as well…of course I can’t recommend them in the southeast owing to the humidity being unwanted 9-10 months of the year here.

Going into the first full winter in our new construction in CZ5, so far the RH has been good hovering around the mid 40s. We’ll see how it goes as we get into the really cold. My bigger issue is VOCs as monitored by the Awair monitor. It’s nearly impossible to keep them below 1000ppb accept when I crack a window. As soon as the window is closed the VOCs climb back up and I have not been able to determine the source. The ERV doesn’t seem to bring them down either. Admittedly it is slightly undersized by ASHRAE standards, but there are only two of us in the house 98% of the time. My other issue with the ERV is that I can smell ozone at times coming from the outlet, I have an email into Fantech about that. Any thoughts on investigated and figuring out the ozone source?

I can’t help you with the ERV / ozone issue, but my general advice to all new construction home owners is to plan to over-ventilate by whatever means works best (run bath fans more, open windows, max out ERVs, etc) for the first year while all the brand new paints, plastics, textiles, etc outgas…kinda like “new car smell”…not good for you!

Thanks John. I’m pretty sure as long as I’m measuring 0 ppm for the water I’m safe. Did the ROCIS use deionized water or 0 ppm water? The burner test picked up 30 ppm in about an hr about 20 feet away from the humidifier. Now they always burn bright blue even with the humidifier running. I tried a non-ultrasonic one before I discovered the zero filters. I bought the InvisiClean brand and by refrigerating the pitcher between uses and starting with RO water I’m still on the original filter after many gallons treated and a years worth of use.

The ROCIS monitoring was without a water filter. It sounds like your solution is a good one. I hope others follow it or use other types of humidifiers. To restate what is said before — seal the air leaks.

This is an important topic for us. We have an 18 month old house in the mountains of NC and the indoor humidity has dropped to 31% today with temps from upper 20s to 40s. It is now 34 degrees and 47% humidity outside. The house was treated with Aerobarrier during construction that resulted in 0.54 ACH. We have two floors (total 3200sf) , two ERVs, and an insulated sealed crawl space and attic. Silver Green Building Certification. The consultants who did the manual J and made other recommendations set the ERVs to run constantly. At night I can “smell” the fresh air through the return next to the bed. There are 2 of us living here with occasional family visitors (not so much because of the pandemic). The consultants insist that we can’t decrease the ERV time. What are your thoughts?

Jean, there’s no way to know your air quality without monitoring it and I think the consultants are playing it safe having you run them at probably what the industry standards are telling them. I would do the same. That said, there are several inexpensive air quality monitors available that can read temp, RH, CO2, VOC, dust particle count and even radon. They report to a phone app and keep a history of whats going on in the house. If you can show a history of good numbers they should be willing to work with you on the ERV schedule.

@Jean, when indoor RH is that low, it’s OK to forego the exhaust fan when showering (open doors afterwards to allow moisture to propagate). Ditto for range hood when cooking with water.

As for the ERV’s… I suggest purchasing a portable CO2 monitor to see if it makes sense to set up the ERV’s on 24-hr timers. If so, you can dial in a schedule through trial-and-error to ensure acceptable CO2 levels.

BTW, since you live in the mountains, you need a CO2 monitor that adjusts for elevation. Virtually all consumer grade CO2 monitors use NDIR sensors that, by definition, require altitude compensation, yet very few are designed to this!

Take Denver for example — a sea-level calibrated NDIR sensor will under-report CO2 concentrations by up to 20% (exact % depends on temperature & barometric pressure). If the monitor is manually calibrated outdoors, this will add a fixed offset so that it’s accurate at 400 ppm. However, without altitude compensation, the under-reporting error will always exceed the offset indoors, and grows larger at higher concentrations (since the error itself is a percentage).

I recently reviewed more than a dozen CO2 monitors that cost under $300 and actually tested six. I found only two that compensate for altitude: The Aranet4, which sells for $249 on Amazon, has internal temperature and pressure sensors that automatically compensate for altitude, temperature and current barometric pressure (currently available from Naltic Supply for $199). The Hydrofarm APCEM2 Autopilot, which costs $107 on Amazon, has an altitude setting where you can set your elevation. This gets you close enough.

Very interesting and informative article, as are all of them!

In June of this year, I had our attic spray foamed with 3″ of closed cell foam (about R-20, which the installer said was all I should do in here in Central VA). The house was built in 1987. All of the old fiberglass insulation was removed from the attic floor. I wanted to air seal and semi-condition the attic because the 2nd floor air handler and duct work are up there.

With that said, this is my first winter with the new attic foam. This morning’s outside air temp is 25 F, the temp in the attic is 60 F, and the RH is 59%. Is that a problem? If so, is there any solution other than running a dehumidifier?

Thanks,

Brian

Since your roof insulation is vapor impermeable, 59% RH, which is simply the result of the lower temperature, is not a problem. But you should continue monitoring and if it exceeds 60% for any length of time, you’ll want to add a small amount of supply air.

IF you end up with persistent excess RH when there’s no heating (or cooling) load, there are several options to address that: If the dew point in conditioned space is lower than the attic dew point, you can add more or more passive transfer grilles, or run your blower on its lowest speed for short periods (some t’stats allow you to schedule FAN ONLY opts). If your house dew point is as high or higher than the attic when attic RH is greater than 60% and there’s no actionable heat or cooling load, then you may have bigger issues that need addressing.

My thinking is that 59% RH isn’t a problem…yet. I agree that it could well result from the lower temperature as mentioned.

However, the 59% RH will likely increase if outdoor temps dip much below 25*F for days at a time. I’m not sure how often that occurs in central VA.

The addition of supply air as suggested by Dave would almost certainly work by raising attic air temperature in turn causing attic air RH to fall. A simpler / less costly approach might be to partially open a scuttle access panel or attic pull down stair assembly thereby allowing some natural convection to occur, thus raising attic air temperature and reducing RH without having to add ductwork.

Another concern with actively conditioning an attic space such as via ducted supply air is that doing so may trigger additional fire safety code requirements such as having to apply an intumescent coating to the foam insulation, or, even more costly, having to install gypsum wallboard (“drywall” or “sheetrock”) as an ignition barrier. From what I’ve been able to determine on that issue, requirements vary widely by jurisdiction.

Thanks so much for your reply. That is very helpful. For now I’m running a box fan up there, to at least keep the air circulating. I’m not sure if that really helps or not. I should have probably added that I don’t have central heat, only central air conditioning. I have no idea why the previous owner opted to install really nice rigid duct work, but only put in a/c. They installed electric base boards for the upstairs heat (down stairs has both heat pump and electric base boards). That is next on my list to address. I was trying to “address the envelope” first. I could probably run the a/c on fan only and get some air exchange, especially since that old duct work is rather leaky.

You are correct that dry wall or some other covering is required by code. I opted not to do that since I’m only using it for storage space.

Thanks so much for your reply. That is very helpful. See my reply below to Curt for some additional information.

Regarding 60% RH. Its certainly not unusual for it to go over 60%. The highest I’ve seen it is 64%. That is in the late summer/early fall when the a/c is not running as much, but there is still high outdoor RH. I may need to try running on fan only, as you have suggested.

Thanks again!

Thanks for writing on this important topic. I was aware of the Sterling chart but not its source so great to have that article.

Yes, the key to management of moisture levels, beyond source control, is tight construction and right ventilation. That’s not easy, as some commenters have noted. I consider a “smart ” ventilation system to be central to a high-performance house. Build Equinox, out of Illinois, has their conditioning ERV which is set to maintain CO2 and VOC levels . When the settings (typically 1000ppm) are met, interior air is recirculated with Merv13 filtration and constant mixing, avoiding over- or under- ventilation and the associated energy and moisture issues. Its an elegant system IMO and well worth looking into.

Thank you for the article. I’m a homeowner trying to put together a lot of building science information. Your description of the role leaks play matches my experience in the last week. On the windy days and nights, it felt very dry even at 38% relative humidity. I ran a humidifier and got the levels up to 50%-54% based on numbers I’d heard from other sources, but the RH would go down quickly when the humidifier stopped running. When the wind calmed down, 50% felt wrong and I’d also learned that some, including you, say 30% RH for the building is best. I’ve not run the humidifier, the RH is SLOWLY going down, at 39% after a day of no humidification. It does not feel too dry.

Does the absolute humidity play a role, would the same building have survived in a very dry climate area? Does it make any difference whether a house is heated to 72 degrees versus 66 degrees for the target relative humidity to protect house and people?

Linda, you’ve come to the right place for building science info for homeowners, especially regarding humidity. Be sure to read the other articles I’ve linked to in this article and in the related articles section below. Now, about your situation and comments here. First, I don’t say 30% RH is best. I say, as with most things building science, it depends. (See also, How to Talk Like a Building Scientist.) 30% RH may be best for your house. The colder the climate, the more likely that’s true. You can get away with higher indoor humidity in warmer places. Even if you have a cold spell and the exterior sheathing gets wet, it doesn’t stay cold long enough in a place like Atlanta, where I live, to keep the sheathing wet long enough to cause problems. What I do say is that you shouldn’t be alarmed by 30% relative humidity.

Yes, the concentration of water vapor matters, too, and it plays a role when the temperatures change. With the same air and water vapor concentration in the house, lowering the temperature from 72F to 66F will increase the relative humidity. And relative humidity is what determines how wet your drywall, sheathing, or other porous materials will get. So lowering the temperature may put your structure at more risk. But again, it depends. There are many variables at play here.

My current house never gets above 20%, and I am hoping I can keep my new super-tight house with an ERV closer to 30%. I will report back in a year.

Beyond climate and RH, the water and type of humidifier matters too. Use only clean water (RO or distilled) in ultrasonic humidifiers. Otherwise mineralized aerosols/PM can be generated. It may be OK to drink minerals, but it’s not healthy to breathe them. https://www.technologynetworks.com/applied-sciences/articles/the-close-to-home-issue-of-humidifiers-and-indoor-air-quality-341176

Yes but RO water is just not good enough. It is 15-30 ppm and puts a bunch of minerals into your air and lungs. It was enough in my house that it showed up as yellow gas burners on the stove. I take RO water and put it thru one of these zero filters. RO water extends the filter life and I end up with 0 ppm and proof for me was that the gas burners went back to bright blue. Less dust too and more healthy for the home occupants as well.

Fred, I was just reading your comment about the minerals we breathe from humidifiers showing up in the products of combustion from your gas cooktop. Wondering which is worse the minerals or the products of combustion?

I think anything that generates small particulates that can get down in your lungs can’t be good and that is true of cooking especially with natural gas (lots of by products other than CO, etc). I try to get my wife to use the hood for that reason but she is stubborn about the noise, lol. One day I’ll convert to electric and we usually use the smaller table top electric oven. And I still have gas furnace (98% eff) and on demand gas water heater. I’ll go to electric when and if this water heater about the time I put in a new larger solar panel system. I’ve had solar since 2006 and my Prius Prime is used mostly in electric mode. My solar panels are going on 16 yrs old and still able to produce 16+ kW-hr on a good day and zero out my bill. Since we hardly use the oven portion of the stove there’s only the burners to worry about and we have a pretty good hood that we use when it’s in use. My wife really doesn’t like cooking on an electric stove but maybe new ones are a lot better.

I had gas for years and loved it but my new (lifetime) favorite appliance is my Dacor induction cooktop. Super fast and responsive and so easy to clean. Gas wasn’t an option at our newly built house and I have no regrets.

Thanks for the good info. My house is heated with 100% wood and the air leakage from a 1980’s house actually helps the wood stove create a draft and function properly. The downside is that using the wood stove brings in dry outside air, thus I have a cold humidifier add enough moisture to give 35-40% makeup moisture. The cold style humidifier uses very little energy and does not have to heat the water to create water vapor.

My problem is getting a good humidity reading. Right now, my Awair unit says the room is at 44%. In the same room, my Ambient Weather sensor says 42%. Next to that my ThermPro unit says 40%. That’s a 10% variation and it is much worse in the summer.

I had a similar issue with temperature readings on these and the thermostat. Eventually, I took an guesstimated average to determine the appropriate offset for the thermostat. Now they are all four in the ballpark as far as temperature readings.

10% is not a bad variation for humidity percentage for residential level sensors. Commercial level equipment is somewhat better, but much more expensive and requires yearly recalibration.